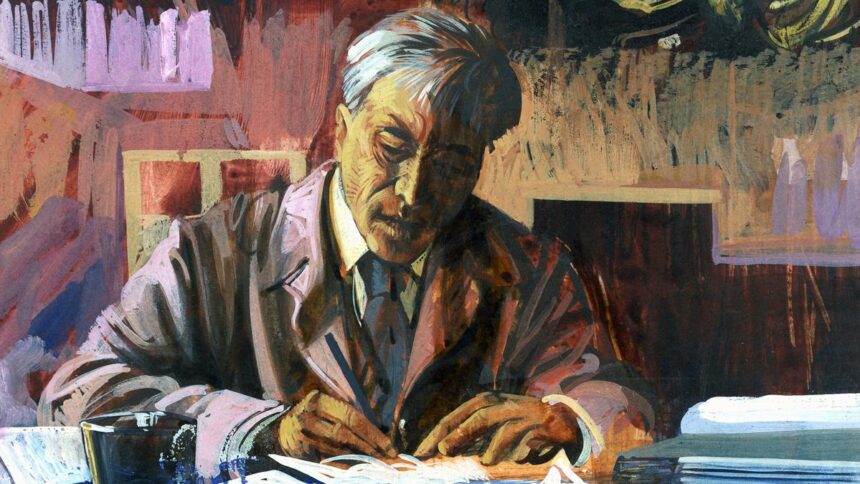

Nobel Prize laureate Boris Pasternak’s painting, which is central to Ismail Kadare’s novel ‘A Dictator Calls’. | Photo credit: Getty Images

For the uninitiated, the tyrant first learned to dominate the story. Fiction, really, is about that. If not, how can we inspire them to buy? His ability to present a larger-than-life, unquestionable, god-like figure is directly proportional to his ability to tell agenda-driven yet astonishing stories so effectively and repeatedly that they attain the status of truth.

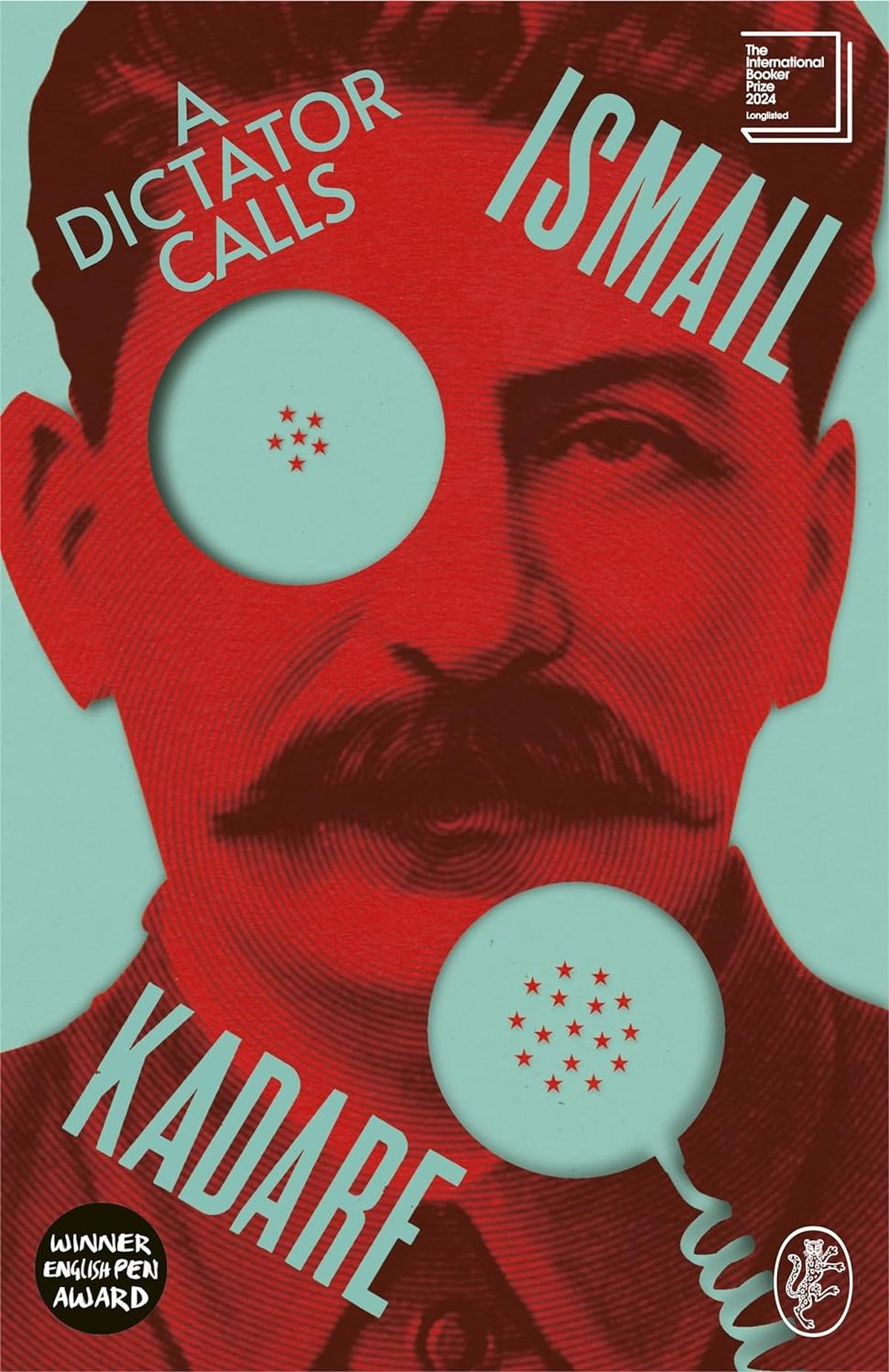

How is a tyrant different from a fiction writer? In the middle of a noisy event, if the artist chooses to remain silent, it shows the characteristic insecurity and cowardice highlighted by the tyrants, why not? The comparison seems exaggerated. But this is one of the main themes of the 2024 International Booker Prize-loglisted novel, The Dictator’s Phone: The Stalin-Pasternak Phone Call Mystery.

Written by Ismail Kadare, inaugural winner of the Man Booker International Prize (2005), and beautifully translated from Albanian by longtime collaborator John Hodgson, A Telephone Dictator hyperfocuses and minutely analyzes 13 versions of the three-minute telephonic conversation between Joseph Stalin and the winner of the Nobel Prize for poetry Boris Pasternak on June 23, 1934, starting with the text of the first KGB archive.

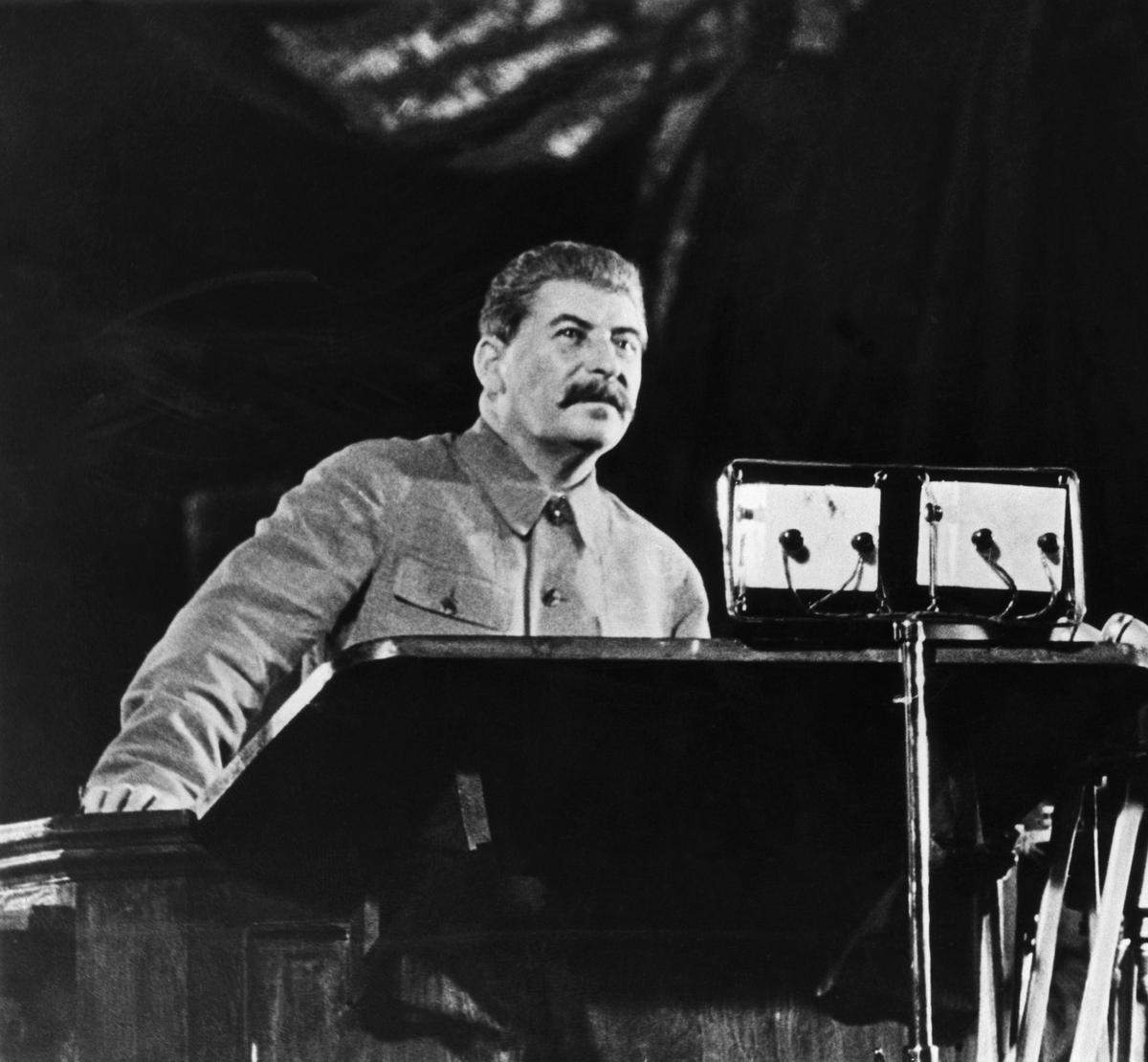

Soviet Russian dictator, Joseph Stalin. | Photo Credit: Bettmann Archives

Insult to injury

The timeline is important here. Just as every authoritarian ruler rages when he finds power slipping out of his hands. The 1930s were a time for Stalin. If the civil and political unrest was not enough, being mocked by the poet – Osip Mandelstam – added insult to injury. Mandelstam wrote and performed a satirical poem, ‘Kremlin Highlander’, in 1933, in the midst of a circle of literary figures, including Pasternak and Anna Akhmatova. He was exiled for these actions.

Kadare wrote in the book: “As he testified later, Pasternak did not wait until the end before interrupting the author (Mandelstam), ‘Forget you have read me … a verse. It is not art, but suicide. I did not participate.’ ” He notes this not to humanize Pasternak, but to expose the fault of the artist, who, like the dictator, is a very worried creature. This is an example: Stalin calls Pasternak to ask for his opinion. After receiving a cowardly response, the dictator tells him that he can defend himself his friend was better and hung up. Pasternak tried to reconnect with Stalin but in vain.

The conversation haunted Pasternak throughout his life. Kadare sent: “What is special here is that both sides, the country and the author, are equally sad.” After establishing this fact, Kadare further explores the relationship between the role of the writer in the dictatorship and how the phenomenon of gossip and constant curiosity makes and does not make the image of the writer (Pasternak) as ‘one of the greatest’.

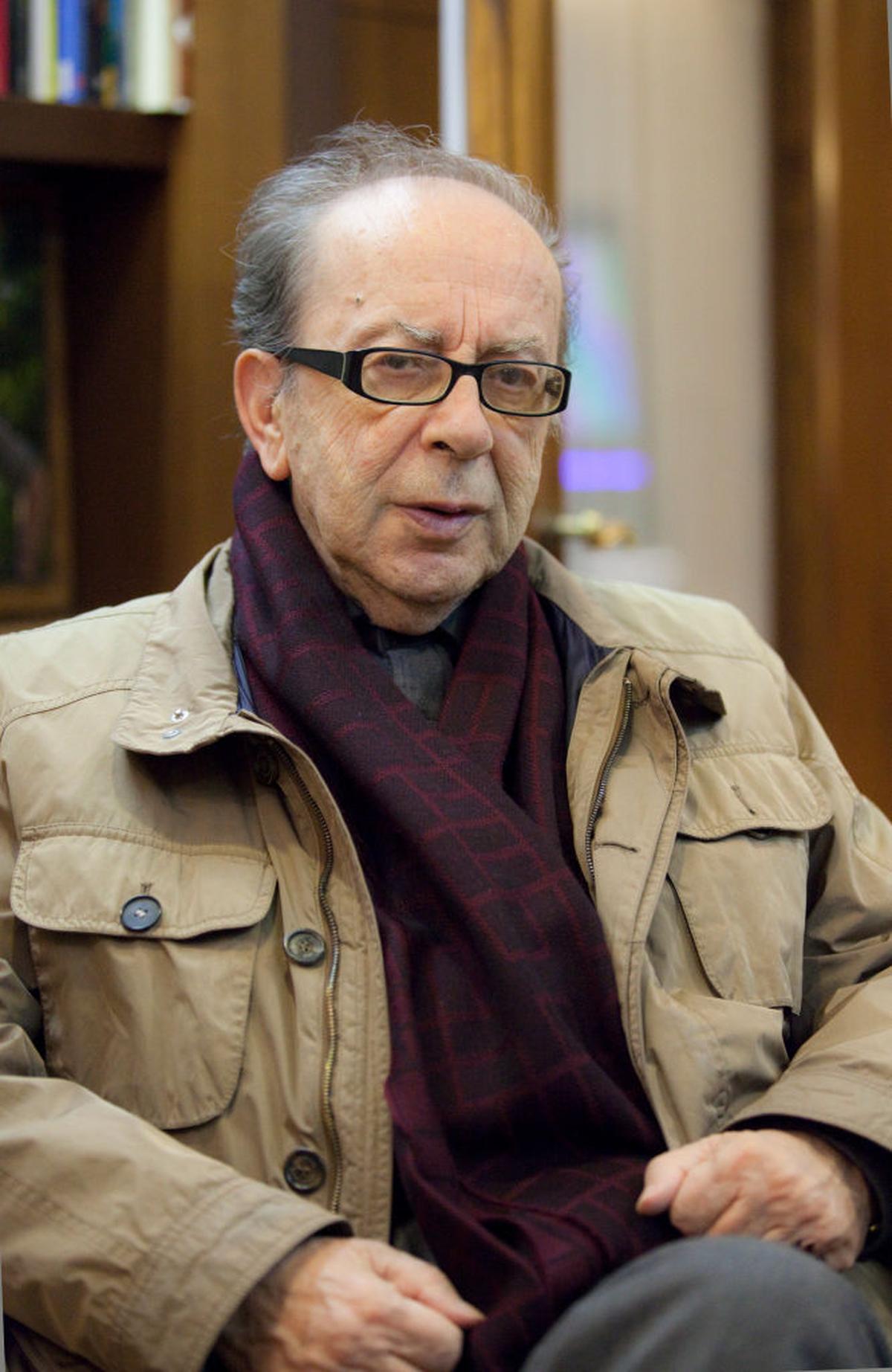

Author Ismail Kadare | Photo credit: Getty Images

Translator John Hodgson | Photo Credit: thebookerprizes.com

Writer-protagonist

Interestingly, the novel begins with the writer protagonist, like Kadare, who studied in the Albanian capital of Tirana and at the Gorky Institute, Moscow, discussing these three minutes in Pasternak’s life because “(they) belong to the same family, the writers”. Meta This literary device helps reduce the distance between the novelist and the protagonist, which is further tested when, as Kadare does in A Dictator Call, the protagonist writes a novel “about memory”, which according to him, is “perfect, complete, which means beautiful and at the same time dead”.

What are Pasternak’s features? yes already. Kadare writes, “Moscow became inevitable from the day it became suitable for art, and our relationship through art could not avoid Pasternak.” But are his editors convinced? Not. The tension between them creates an exciting moment in this novel, making readers want to know whether the author will censor himself or reject the possibility of letting the book come out.

However, before answering this question, Kadare deftly steers the conversation to a phone call between Stalin and Pasternak. Curiosity and rumors play a major role here, so there are 13 versions. As Kadare wrote: “Anyone who tries to find the truth, who first thinks that thirteen versions are too many, may end up thinking that this is not enough!” This further helps the author to focus on important questions related to art and politics that the artist chooses to champion, because there is a lack of truth that only fiction can uncover.

The reviewer is a Delhi-based queer writer and freelance journalist. Instagram/X: @writerly_life

A Telephone Dictator