Rev. Charles Duplessis walks by his solar panel-topped house in New Orleans’ Lower Ninth Ward neighborhood on Friday, Feb. 25, 2022. The Environmental Protection Agency this week awarded the city nearly $50 million to help pay for installing solar on low to middle income homes.

Halle Parker/WWNO

hide caption

toggle caption

Halle Parker/WWNO

After Hurricane Ida struck in 2022, the city of New Orleans went dark. The electric grid failed, spurring calls for more energy independence through measures like rooftop solar.

On Monday, the Environmental Protection Agency awarded the city nearly $50 million to help pay for installing solar on low to middle income homes as part of a program to cut the country’s climate pollution. The project gives the city a way to adapt as a changing climate yields stronger hurricanes while also emitting fewer emissions that cause the planet to warm. The city also plans to green up underserved areas with trees and build out its lackluster bike lane system to provide an alternative to cars.

New Orleans’ Deputy Chief Resilience Officer Greg Nichols called the federal funding “historic.”

“(This,) the City’s largest ever investment in climate action, is a testament to our collaborative efforts and unwavering dedication to addressing climate change,” he said.

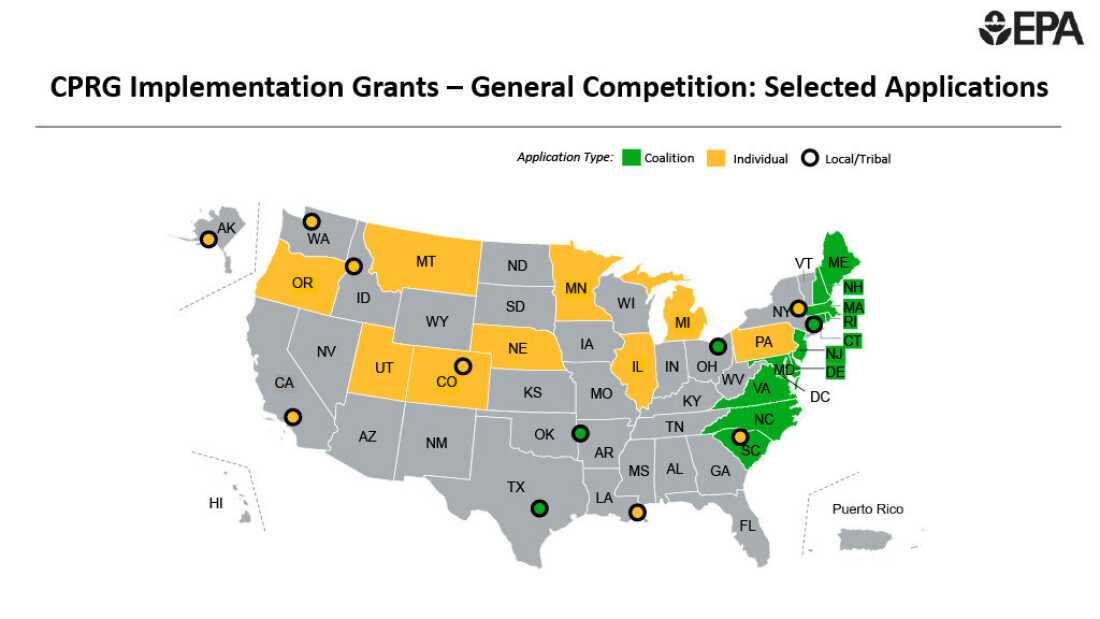

New Orleans is one of 82 cities and 45 states that applied for funds from a $4.3 billion grant program aimed at encouraging local action to help address human-driven climate change. The EPA selected 25 projects out of 300 applications.

“What this proves is what the president has been very clear about, which is, in the United States, when we come together, there’s nothing we can’t accomplish,” said White House Climate Advisor Ali Zaidi. “There are no tons (of greenhouse gas emissions) too tough to abate. No pollution we have to settle for.”

According to the EPA, the projects will reduce the country’s planet-warming emissions by almost 1 billion metric tons by 2050 — the equivalent of removing the average yearly energy use needed for 5 million homes over 25 years.

The more than two dozen projects are spread across 30 states and cover a suite of initiatives.

In Utah, $75 million will fund several measures from expanding electric vehicles to reducing methane emissions from oil and gas production. Oregon will receive nearly $200 millionto reduce climate pollution in three major sectors including buildings and transportation. The Nez Perce Tribe in Idaho and Oregon was the only tribe chosen to receive a grant, and they will use more than $37 million to improve energy efficiency and renewable energy infrastructure.

On the East Coast, a coalition of states led by North Carolina will look to store carbon in lands used for agriculture as well as natural places like wetlands, with more than $400 million.

The EPA awarded $4.3 billion in grants to help communities implement projects that will reduce climate pollution. The money will fund projects in 30 states.

Environmental Protection Agency/EPA

hide caption

toggle caption

Environmental Protection Agency/EPA

But the billions granted Monday will only cut the nation’s total climate pollution by less than a percent in the coming decades. While that might seem like a drop in the bucket, Rocky Mountain Institute climate researcher Wendy Jaglom-Kurtz said these projects will have a larger impact beyond lowering emissions.

“It’s important to remember that this money is funding much more than just climate pollution reduction,” she said. “It’s providing investments in communities, new jobs, cost savings for everyday Americans, improved air quality, … better health outcomes.”

The grants are part of the Biden administration’s Climate Pollution Reduction Grant Program (CPRG) — a sweeping effort created under the country’s largest investment in climate action ever through the Inflation Reduction Act.

To compete for these federal dollars, states, tribes, and cities like New Orleans had to submit their own road maps for reducing emissions known as climate action plans.

The lure of the multi-billion dollar grant program incentivized states, cities, and tribes that lacked climate action plans to submit their own earlier this year. Now, nearly every state has charted a plan for lowering its climate pollution and adapting to the extreme changes caused by a warming planet.

“It is providing some momentum and initiative that hasn’t existed before at the state level that we’re really excited about,” said Jaglom-Kurtz.

Seed money for the climate

The $4.3 billion announcement only funded a fraction of the projects proposed by states, cities, and tribes. However, the process helped more than half of states start on climate action plans that either did not exist or were stalled.

The rural, conservative state of Montana, for example, had a climate plan created under a Democratic governor in 2020, but it was shelved when Republican Gov. Greg Gianforte came into office.

Montana’s efforts were rewarded. The state will receive nearly $50 million to improve forest management, address wildfires, and extinguish coal seam fires, which are underground and emit large amounts of carbon dioxide and toxic fumes. The money will also help lower agricultural pollution and improve soil health.

The EPA awarded Montana nearly $50 million to improve forest management and address wildfires.

Ellis Juhlin/Montana Public Radio

hide caption

toggle caption

Ellis Juhlin/Montana Public Radio

But Montana’s other proposals, including its push to update aging school buildings to improve energy efficiency, did not get funding. In a written statement, Gov. Gianforte said he was grateful for the investments in forest health and agriculture, but displeased to see schools left out of the funding. “Our state agencies work diligently to serve Montanans, and ensure we maintain the best environments to live, work, and learn,” he wrote. “Our states deserve better coordination from the federal government to best serve our communities and our students.”

Jennifer Macedonia is the EPA’s deputy assistant administrator for implementation within the Office of Air and Radiation, which oversees the CPRG grant program. Though the plans are non-binding, she said the agency hopes states and other governments will use their climate action plans and the projects they pitched to move forward regardless of grant funding.

“Many of the options that are available to reduce greenhouse gasses are cost-effective and may even have a high return on investment,” Macedonia said, pointing to benefits such as improved air quality and public health benefits. “These climate action plans connect the dots on where there are opportunities to make progress on multiple fronts.”

The grant money is part of a larger push to get communities to plan for a warming world. By having climate action plans in place, Macedonia and Jaglom-Kurtz said local officials can take advantage of other federal funding through the Inflation Reduction Act and Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

“It’s great to see these projects move forward and we’re even more excited by the hundreds of projects and partnerships that this program catalyzed that can now leverage other federal incentives and private funding to bring wide-ranging benefits to people and communities across the country,” said Jaglom-Kurtz.

“A gold mine of information”

For climate researchers like Jaglom-Kurtz, the nearly 7,000 pages worth of state plans, including Washington D.C. and Puerto Rico, is a treasure trove. As a manager in Rocky Mountain Institute’s U.S. States program, Jaglom-Kurtz said the documents offer a unique window into how different states approach climate action.

“It’s this huge gold mine of information,” she said.

Jaglom-Kurtz, along with others in the research community, will use these plans to determine trends in what states are prioritizing and what sectors might slip through the cracks. For instance, 18 state plans emphasized the importance of equity in their project planning.

“That was actually the most common of the things that we looked at,” Jaglom-Kurtz said.

She said updating buildings and transportation needs was another common theme that emerged. Others signaled interest in projects that grow the economy and create new jobs. Jaglom-Kurtz noticed several states included projects involving microgrids – or small-scale renewable energy projects that include their own battery for storage, independent from the larger electrical grid, like New Orleans’ rooftop solar plan.

Proposed projects that made the greatest dent in emissions targeted the industrial sector. The Rocky Mountain Institute’s analysis found that Louisiana, a major hub for the petrochemical, oil, and gas industries, would create close to 30% less climate pollution if the state’s proposals for increasing energy efficiency in large industrial facilities and capturing the remaining carbon are realized. None of those projects, however, received grant funding through the EPA.

Some states opted out

Not all states responded to the EPA’s call to develop climate plans and submit projects for grant funding. Florida was one of five conservative states — including Kentucky, Iowa, Wyoming, and Kansas — to opt out of the grant program.

Political analysts have watched Florida’s governor and attorney general repeatedly turn down opportunities for federal money. This year, Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis removed the phrase “climate change” from state policy, despite the state’s risk from marine heatwaves, rising seas, and stronger hurricanes fueled by global warming.

But even though Florida and other states opted out, the Biden administration designed the program to allow cities to apply instead— a lesson they learned from Obamacare Medicaid expansion.

“(Florida) had to make that decision based on factors that we might not be privy to. But at the end of the day, we still have a responsibility to our local jurisdictions,” said Cara Serra, the director of resiliency for the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council.

Tampa, along with Orlando, Jacksonville, and Sarasota, formed a coalition representing 40% of the state’s population to submit plans. Tampa, for example, wanted to bring more solar power to the grid to replace fossil fuels used to power homes and electrify public transportation. However, none of the cities received grant funding for their projects.

Just the beginning

The 25 projects funded by the EPA’s grant program will not be enough for the country to meet its climate goals of net zero emissions no later than 2050. But the climate action plans could tackle a larger share of emissions if states, cities and tribes implement them.

It’s still unclear how much greenhouse gas emissions each climate plan would reduce, but a new analysis by the Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) starts to answer that question. Researchers found that if all 45 state plans – plus Washington D.C. and Puerto Rico — were fully implemented, the country’s total greenhouse gas emissions could be reduced by 7% by 2030. That doesn’t account for plans submitted by cities and tribes or the fact that plans did not have to set net-zero emission goals.

Drew Veysey, an RMI analyst who worked on the report, stressed that while 7% might sound small, it makes a difference.

“This is a significant amount of emissions of pollution, it’s equivalent to turning off about half of the methane power plants in the United States,” Veysey said.

Jaglom-Kurtz said she believes these climate plans have the potential to take “a meaningful bite out of 2030 emissions.” Reducing climate pollution in the U.S. is a big, complex problem that will require more than a single program to address, she said.

“It’s one part of a much bigger puzzle that is moving forward,” said Jaglom-Kurtz.

The participating states, cities, and tribes are also expected to submit more comprehensive climate action plans next year to build on their initial plans — ones that are expected to result in even larger cuts in climate pollution. Meanwhile, the EPA is expected to announce more grant funding for tribes and U.S. territories later this summer.