Book Review

Paradise Bandits: The Hole-in-the-Wall Gang and the Final Chapter of the Wild West

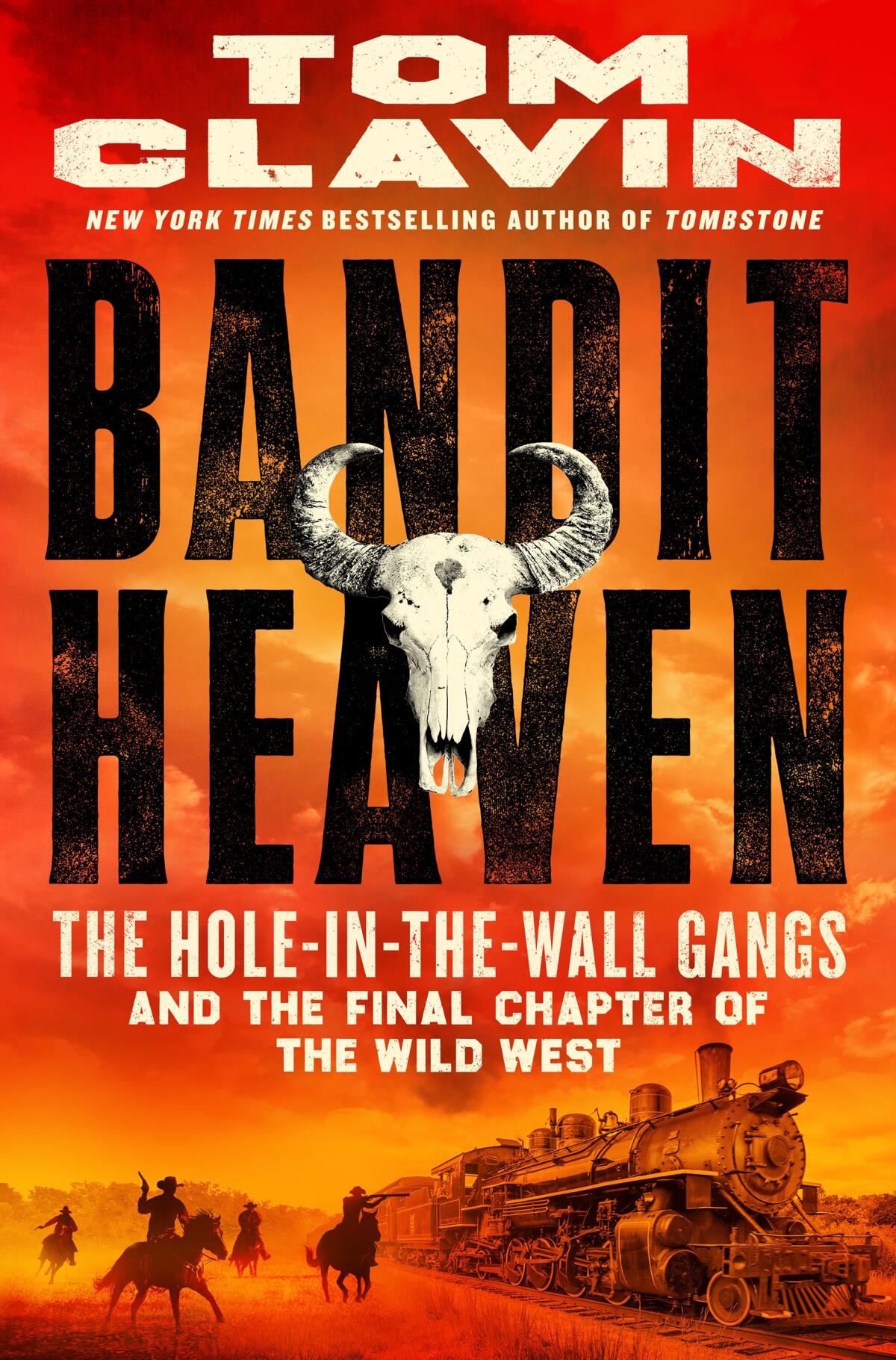

By Tom Clavin

St. Martin’s Press: 304 pages, $30

If you buy a book linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, which costs support independent bookstores.

We love the mythology of Western villains and their fun nicknames, which often include the moniker “Kid” (Billy the Kid, the Sundance Kid or, if you’re a fan of John Ford’s “Stagecoach,” Kid Ringo). Tom Clavin, author of several books about the Old West, including “Dodge City,” “Tombstone” and the new “Bandit Heaven,” after something else elusive: reality, or the closest to them. He is not a revisionist historian in the vein of, say, Richard Slotkin, whose books, including “Gunfighter Nation” and “Fatal Environment,” examine the foundation, blood-drenched myths of the United States. But the real stories Clavin tells — and “Bandit’s Paradise” often reads like a series of fun yarns — are based on deep research.

That doesn’t mean they aren’t fun. In telling the story of three late 19th century hideouts in Wyoming and Utah – Robbers Roost, Brown’s Hole and Hole-in-the-Wall – “Bandit Heaven” reminds us how colorful language is used to describe even the most dire situations. For example, the winter of 1886-87 was brutal, killing people and about 90% of cattle in northern Wyoming, Montana and the Dakota Territory, which became known as the Big Die-Up. If you’re going to leave, you might as well go to the so-called.

Sometimes a random place name is enough for fun. I’m rather partial to the town of Chugwater, Wyo., where Two Bar Ranch is from. And of course there are naughty names and varmints themselves. Cherokee Bangs. George “Big Nose” Parrott (that’s just bad). George “Flatnose” Currie (what’s better?).

The press may join in on the action. When homesteaders Ella Watson and James Avrell were kidnapped at the hands of avaricious ranchers who wanted their land, one newspaper headline summed up the crime: “Blaspheming Border Beauty Barbarously Boosted Branchward.”

As Clavin explains, violence in the period is often perpetrated by large land owner consortiums intent on swallowing their small competition. The year 1891 begins the Johnson County War, in which Wyoming cattle barons hire killing squads to eliminate small ranchers who have the temerity to build barbed wire fences around their land and cattle. Barons often have law enforcement in their pockets; as Clavin writes, “Even in the last days of the Wild West, there may be a thin line between lawyer and criminal.”

The battle of Johnson County was the basis of the 1980 film “Heaven’s Gate,” a notorious failure that bankrupted the studio, United Artists, but remained open to reconsideration. The ranchers’ practice of cutting through barbed wire fences is a fun plot point in Gary Cooper’s 1940 western “The Westerner.” But the true movie stars of “Bandit Heaven” are Bob Parker and Harry Longabaugh, better known as Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Here, too, Clavin applies some myths. Parker/Cassidy is definitely riding Lonabaugh/Sundance, but his “best friend and main sidekick in the criminal gang he leads” is a different person, named Elzy Lay, who is not blessed with a pithy moniker. The somewhat glib 1969 film about Butch and Sundance (which came out the same year as the superior western about the end of the frontier, “The Wild Bunch”), had solidified the conception of the duo as charming quipsters, a description that seems to have at least some basis in reality.

In the words of Ford’s “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,” “When legends become reality, print legends.” But Clavin is generally more interested in reality, and if he does not have to translate it with poetry or great imagination, he knows how to grind out piece by piece, episode by episode. They eventually reach Butch and Sundance, the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang and their pursuers, including Pinkerton detective Charlie Siringo, who infiltrates the gang (and is also at the scene of the 1886 Haymarket bombing and its aftermath in Chicago). When he’s not going after Western criminals, Siringo gathers union members; at times it is hard to say which struck another fear in the heart of the government and law enforcement.

Clavin explains that cattle rustling is a routine operation in modern times, often seen as a form of skimming of large ranchers by cowboys hired to work their livestock. Sometimes crime went unpunished in the last days of the frontier. And sometimes revenge is done with ferocity. “Bandit Heaven” is at its best when Clavin drops a macabrely detailed anecdote. Which brings us back to our friend George “Big Nose” Parrott.

This unfortunate criminal was hanged from the crossbeam of a telephone pole after he and a gang of train robbers gunned down a pair of lawmen and Parrott trying to escape from jail. Then it got weird. Two doctors decide to study the brain and possible criminal tendencies. Clavin writes: “A death mask of Parrott’s face was made and the skin from his thigh and chest was removed. His skin, including the dead man’s nipples, was sent to a tannery in Denver, where medical bags and shoes were made. One of the doctors, John Osborne, wore the shoes when he became the first Democratic governor of Wyoming in 1893.

Who needs legends when historical records offer such riches?

Chris Vognar is a freelance culture writer.