No one knows when he has crossed the invisible line into alcoholism. Ironically, I always knew intuitively that I could get into trouble, because substance use—especially with alcohol—ran through both sides of my family, for generations.

What surprises people is that I didn’t start drinking until I was 24. I tried drinking a couple of times when I was 18, but I realized right away that I didn’t like it, so I chose to lower my alcohol intake. However, my perspective changed when my best friend at the time thought it would be fun to mix vodka into diet coke without my knowledge.

After that happened, I started drinking regularly, and within a year, I was drinking two or three glasses of wine every evening while working from home. By the time I was 27 years old, this habit had gradually increased to two or three bottles.

After I reached 30, I realized that my drinking habits were quite large, but I ignored how it could affect me. My only concern is that I have lost the habit of going to the gym, although until now I manage a gym session every day.

As the managing director of the charity I have founded, Men Get Eating Disorders Too!” I seem to be “functioning” -even dysfunctionally – which in retrospect is probably one of the early signs of my alcoholism. signs that my drinking is “overspilling,” why would I become more wise?

The first sign that drinking has caught up with me came 36 hours after I decided to stop, with the intention of getting back to the gym. At this point, I hadn’t gone more than twelve hours without touching a drop. While in London on a very hot day in July 2016, I could not ignore how bad I was feeling. I was sweltering, with sweat dripping from me as I traveled to the ground.

As I stood up to get off the train, I noticed that my body wasn’t doing what I told it to and my reaction was slow. That was the first sign I knew something was wrong. It was as if there was a disconnect between the brain, the body, and the ability to move—almost like an out-of-body experience. Getting off the train, I reached street level and got out.

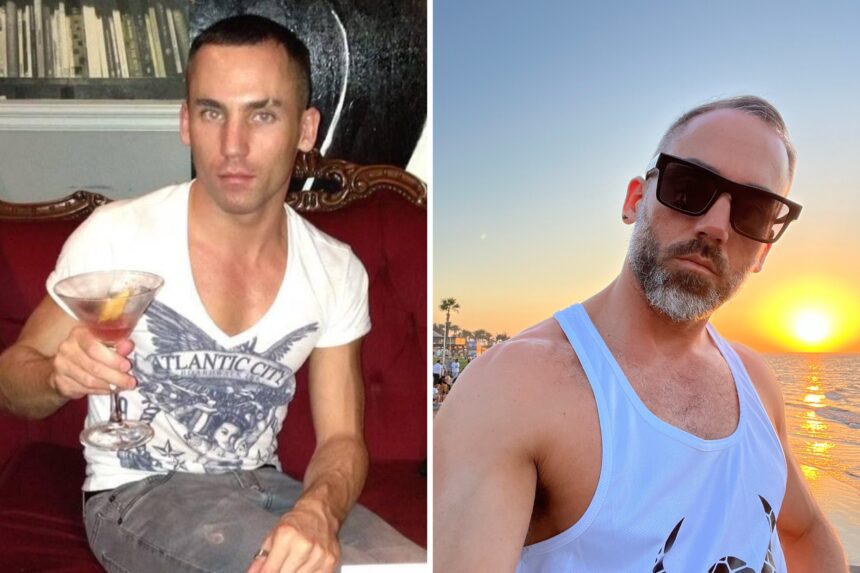

Sam Thomas

My anxiety was through the roof and, in a panic, I found sanctuary in a coffee shop in front of the station. At this point, I tried to hold a glass of water in my mouth to drink but I kept pouring water over myself.

A lady sitting at the opposite table was looking at me curiously. “Do you need help? You look like you’re in trouble?” she said, after a short while. She introduced herself and it turned out she was a death nurse from St Mary’s Hospital. “Do you know what’s wrong with you?” he asked.

“No,” I answered shortly but sadly. I just thought I might have some kind of reaction, but I’m not allergic. In the next minute, I died, and then I was in an ambulance to the hospital.

Unfortunately, it will take until the third subsequent hospital visit in November 2016 to confirm that the previous episode of the disease is the cause of alcohol withdrawal. “You’ve crossed the threshold,” said a specialist doctor from the local drug and alcohol service. “You should be referred for detox, possibly as an inpatient because of your relapse,” he said.

Until now, I had no idea that drinking was making me sick – more specifically, cutting down on drinking too quickly or stopping drinking too quickly – for example, “cold turkey”. “It’s very important that you keep drinking to prevent another episode,” he insists, which at first sounds like confusing medical advice.

Admittedly, it took me a while to wrap my head around this, not knowing that my nervous system would go into shock—from alcohol withdrawal—if I went more than a day without drinking.

The most severe symptoms are severe hallucinations – sometimes called “delirium tremens”. He was increasingly relapsed after repeated detoxes, and his symptoms worsened due to malnutrition. Usually, the hallucinations are of spiders and crab-like creatures that I can physically feel crawling all over them. This episode was scary, but I don’t remember how long it lasted.

In November 2019, I had my last hallucination involving a bat after trying to detox again. Eight days later I was admitted through confusion because of the drugs they gave me to get rid of alcohol. All I remember was that the first few days were very difficult, but I managed to get through it. Eventually, my symptoms subsided, and I finally began to see a future for myself. However, detoxification is “easy”, and the real work will begin when I get home.

There will be many people like me who “cross the threshold” and can suffer in silence. They may have unexplained symptoms after a few days of abstinence. Or maybe he caved and went back to drink, I don’t know why. Upon reflection, if I had known the brutal reality of alcoholism, I would have been able to complete my recovery quickly.

Looking back, I now consider myself lucky to be alive. What I know now is that if my dependence on alcohol continues, I will be knocking on the door of the devil. The last detox was especially challenging: it was a strong reminder of how close I was. For almost five years now, I want to share my story so others know they are not alone.

I have now been sober for two years. If I’ve learned anything, it’s that addiction thrives in isolation and secrecy, which is all the more reason we need to talk about it without shame. To ensure many more years of progress, I need to make sure that recovery is bigger than addiction.

Sam Thomas is a writer, campaigner and public speaker. He is based in Brighton, England

All opinions expressed are solely those of the authors.

Do you have a unique experience or personal story to share? See our Reader Submissions Guide and email the My Turn team at myturn@newsweek.com.