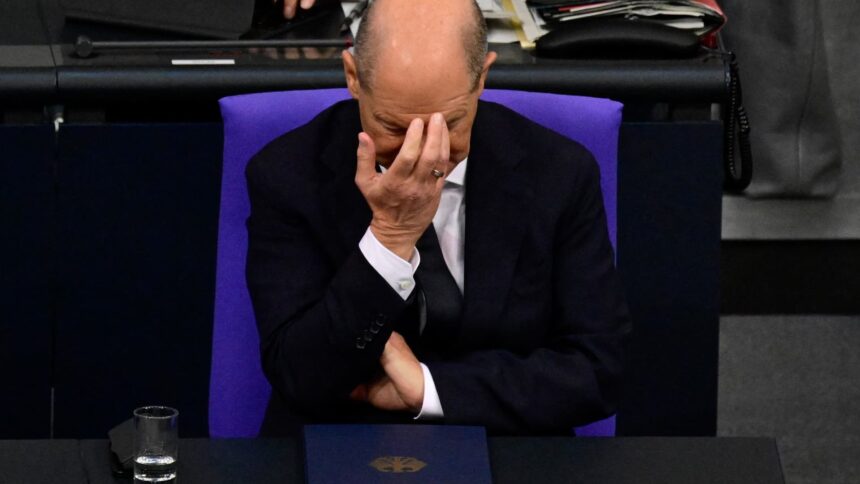

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz attends the session on November 13, 2024 in the Bundestag.

John Macdougall | Afp | Getty Images

When Germany’s government collapsed earlier this month, clashes within the former governing coalition over economic policy and the budget were widely cited as a key factor – with the country’s debt brake playing a major role.

Former Minister of Finance Christian Lindner, whose sacking is a tipping point for the ruling coalition breaking up, told the press in early November that German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has demanded a break to brake the debt, a request he could not accept.

Scholz had fired Lindner the same day, saying the former finance minister seemed unwilling to cooperate with Scholz’s suggestions for Germany’s 2025 budget. Scholz claims that his plan incorporates the ideas of Lindner’s party, but also clearly shows the need for more financial flexibility.

Tensions over fiscal policy have long been rising, fueled by growing concerns about the state of the country’s economy, which has been in recession for several quarters. The second reading of third quarter GDP released on Friday showed growth of 0.1% from the previous quarter.

So the three-year coalition between Scholz’ social democratic party (SPD), the Green Party and Lindner’s free democratic party (FDP) collapsed. Germany now faces early elections in February.

But what is a debt brake and why is it so controversial?

What is debt brake?

The German debt brake, or ‘Schuldenbremse,’ is a fiscal rule that is part of the German constitution. The debt brake limits the amount of debt the government can incur, and dictates that the size of the federal government’s structural budget deficit must not exceed 0.35% of the country’s annual gross domestic product.

It was agreed in 2009 in response to the 2008 financial crisis and the extremely high debt of the German government at the time.

In some exceptional circumstances, the debt brake can be issued – this happened for example during the Covid-19 pandemic.

German government debt is just over 60% of gross domestic product, according to the European Commission, which is lower than the debt-to-GDP ratio of other eurozone countries.

When the debt brake was first implemented, its supporters claimed that it would ensure a sustainable and responsible approach to public finance and spending. To this day, this remains a popular argument in support of the policy.

Critics meanwhile, said the debt brake is too restrictive, and has hampered the investment that is needed for a successful future.

Philippa Sigl-Glöckner, founder and director of think tank Dezernat Zukunft, told CNBC’s Annette Weisbach last week that the debt brake has led to “a huge lack of investment.”

Infrastructure like Germany’s rail network and education are now suffering, he said. “And for me, it’s a consequence of being in debt,” he said.

Point of contention

In the current leadership coalition, views on the debt brake differ.

Scholz’ SPD for example has repeatedly advocated for the reform of the debt brake, calling for a wide scope for what can be seen as a useful emergency to suspend it, for example climate change and the Russian-Ukrainian war.

FDP Lindner supports the view that the debt brake rules must be respected and says that the lingering effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, the climate emergency and the war in Ukraine are a long-term challenge for the government rather than an emergency. This has marked a change in policy however, because the FDP abstained in the 2009 vote to add a debt brake to the German constitution.

The debt brake became more controversial after Germany’s constitutional court ruled last year that the government was not authorized to issue emergency loans again during the Covid-19 pandemic to the budget. At the time, some observers and government figures said the climate crisis was also an emergency, but the court’s decision stood.

The ruling, which imposed a “strict interpretation of the debt brake,” was a major contributor to increasing disputes in the former coalition over “how to deal with the lack of fiscal space,” Holger Schmieding, chief economist at Berenberg, told CNBC.

But while the debt brake was an important factor in the government, Carsten Brzeski, head of global macro at ING, said other factors were also at play.

“Lindner is almost religiously clinging to the debt brake, although he has shown some flexibility in the past, suggesting that there may be a political motive,” he told CNBC. “I think the government collapsed mainly for political reasons and personal tensions.”

The future of debt brakes

While attention is now on the upcoming election, questions about the future of the debt brake in the new coalition government have arisen. Opinion polls show that the current opposition party, the Christian Democratic Party, will secure the largest share of the vote and therefore send the next chancellor.

Berenberg’s Schmieding said that if elected, the CDU would enter a coalition and strike a deal with a centre-left party such as the SPD or the Green party.

He predicted that the CDU, along with its Bavarian affiliate party CSU, will agree “to modest reforms of the debt brake to create fiscal space for military spending and other investments. In return, the center-left will agree to some pro-growth reforms including pruning welfare benefits , less generous conditions for early retirement and lower business taxes.”

ING Brzeski also expects the debt brake to ease, but points out that structural changes to the law require a two-thirds majority in parliament because fiscal rules are part of the constitution – meaning the outcome will also depend on a larger parliament. up.

Others have been more skeptical, with Marcel Fratzscher, president of DIW Berlin last week telling CNBC’s Weisbach that he believes the new government “will not touch” the debt brake.

Public support for this is high, and the country “has an obsession with savings and debt,” he said. Symbolic changes can come, such as how the structural component of the debt brake is calculated, he explained – “but not the fundamental changes that we urgently need in Germany to push public investment.”

Meanwhile, Brzeski argued that even without major debt brake reforms, there is still some movement in Germany’s fiscal policy, for example through special vehicles designed for investment funds.

“In any case, I expect an additional fiscal stimulus of 1% to 2% of GDP over the next five to ten years. This will finally close the huge investment gap, which has developed over the past ten years.”