When kindergarten teacher Cynthia Farrow was looking for a community where she could raise her family and get a house with enough space for a few horses, she settled on the desert town of Littlerock in the Antelope Valley.

Farrow, along with her husband Gary and their 10-year-old son and 3-year-old daughter bought a house in 1996 in a village about 50 miles northeast of Los Angeles.

“We were priced out of so many places except here in AV,” Farrow said, referring to Antelope Valley. “This is a dream place and we found a community here. But, unfortunately, that also attracts other people here.

Affordability, low population density and space between homes and properties – often measured in acres – also attract authorities and courts across the country looking to relocate ex-sex offenders who have been paroled or recently released.

Antelope Valley residents like Farrow and others who have fought the placement of these offenders have been turned on by the potential of moving Christopher Hubbart, a.k.a. “The Pillowcase Rapist,” to the Juniper Hills community.

They see the placement and two others in 2021 as an escalation in the relocation of violent sexual predators into their communities.

LA County Superior Court Judge Robert Harrison is considering whether to approve the move, after receiving 600 letters and petitions Tuesday in opposition from area residents. Los Angeles County Kab. Atty. George Gascon, Supervisor Kathryn Barger and other officials have spoken out as well.

Farrow, who lives directly across the street from the violent sexual predator who previously moved, Calvin Lynn Grassmier, attended the court in Hollywood along with friends Mary Jeters, Linda Adams and Diane Swick.

Antelope Valley residents Diane Swick, center, and Mary Jeters hug outside the Hollywood District Court after attending a hearing to determine a placement recommendation for Christopher Hubbart.

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

“We’re writing petitions, we’re attending court cases, we’re doing everything we can to stop the move here,” Farrow said. “Enough is enough. We deserve respect.”

Placement of sex offenders in the Antelope Valley, an area that includes around 545,000 people with the two big cities of Palmdale and Lancaster, has been well-documented.

The Antelope Valley Times labeled the area as “dump the soil for the type of offender” in 2014 when it listed 876 registered sex offenders in the area. That’s about 6% of the sex offender population in Los Angeles County (11,520) at the time.

California state Sen. Scott Wilk (R-Antelope Valley) tried to address the “dumping of sex offenders” into their communities in 2018 by introducing legislation that would require released inmates or released sex offenders to return “through every possible effort ” to the city of last legal residence or a geographical location close to where a person has family, social or economic ties.

“This change in law is good news for people living in rural and affordable areas of California, such as the Victor and Antelope valleys,” Wilk said in August 2018. “It’s the families that live in the area that are shouldering the burden of housing and rehabilitating the state’s sex offenders. That’s all about to change.”

The release of sex offenders results in a variety of provisions.

Megan’s Law 2004 create a publicly accessible database to show where registered sex offenders live. Jessica’s Lawpassed in 2006, it requires prohibiting parolees from living within 2,000 feet of a school or park where children congregate.

But for some Antelope Valley residents, Wilk’s law hasn’t changed much.

“What you get is a case like Christopher Hubbart, a violent man who the court says should be released,” said Jeters, who opposes the local placement of sexually violent predators and who runs a Facebook group. There is no SVP in the Antelope Valley. “A lot of people think there’s nothing here, that we’re quiet, so they try to put them here.”

In 2021, an LA County Superior Court judge released sex offender Calvin Lynn Grassmier to the city Little Rock, although thousands of citizens opposed it. In the same year, Lawtis Donald Rhoden, who sexually assault some girls of agealso placed in the unincorporated county area near Lancaster.

“What’s changed over the last few years is the number of really violent sexual predators that have moved in,” said Jeters, 62, who lives within six miles of all three.

Hubbart earned the nickname “Pillowcase Rape” because he covered his victim’s head with a pillowcase while raping and assaulting her.

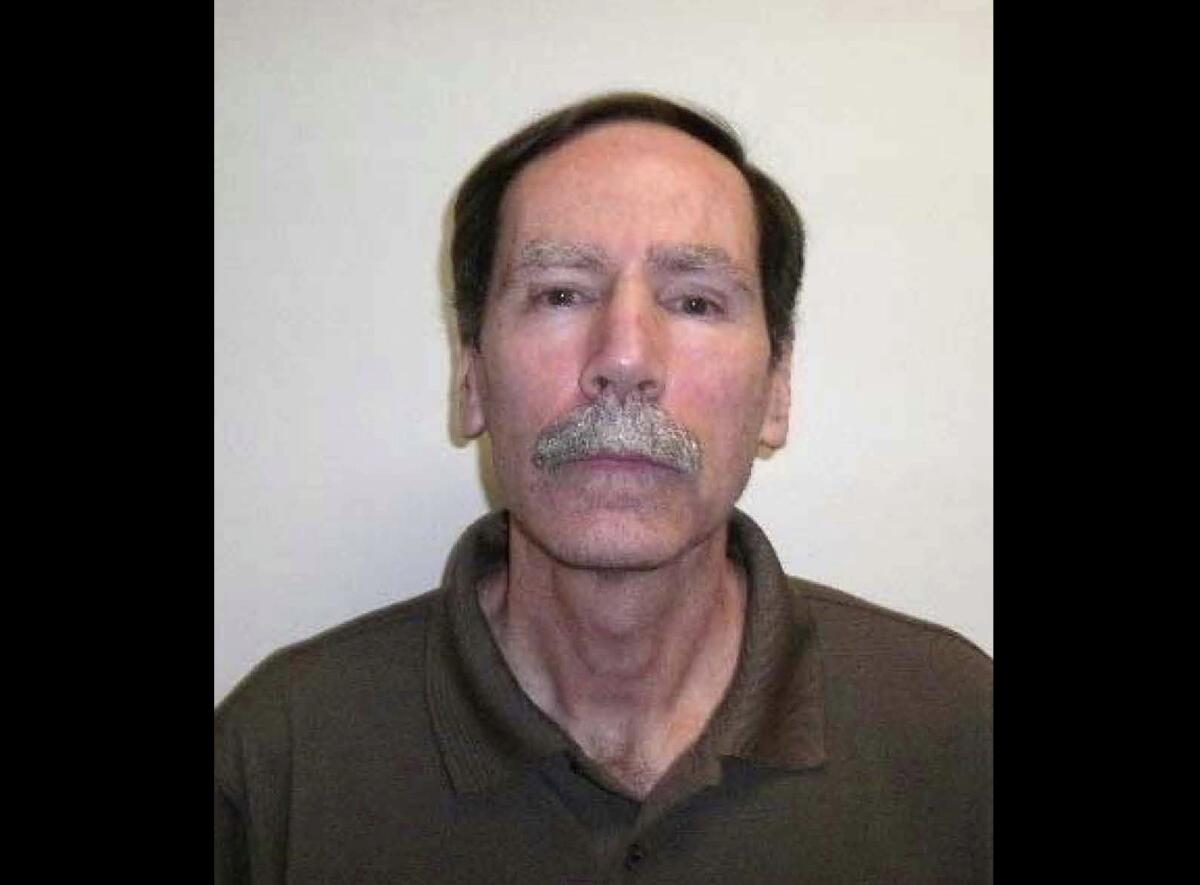

This undated law enforcement order file photo, released by the LA County Sheriff’s Department in 2014, shows Christopher Hubbart.

(Uncredited / Associated Press)

He assaulted and raped women in Glendora, Hacienda Heights, Rowland Heights and Pomona, making headlines throughout 1972.

A 21-year-old Claremont furniture worker was eventually arrested after a suspicious person was spotted lurking near Brea. He was charged with rape, sodomy and attempted rape, eventually pleading guilty to several charges before being sent to a state hospital. He was released in 1979, moved to the Bay Area and was arrested again two years later and convicted of rape, burglary and other crimes.

Hubbart eventually admitted to 44 sexual assaults over an 18-year period.

Hubbart was committed to the Department of State Hospital in 2000 for mental health evaluation and treatment, as required for sex offenders six months after release. DSH provided Hubbart with years of sex offender treatment.

Hubbart was first released in 2014 to the Lake Los Angeles area near Palmdale in a conditional release program, despite the opposition of the former LA County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey. He lived there for two years before violating the terms of his release and being sent back to DSH Coalinga State Hospital.

DSH declined to disclose the nature of the breach due to patient privacy laws.

Five years later, the court recommended that Hubbart be given another chance at parole.

In 2022, the Santa Clara County Superior Court determined that Hubbart must live in Los Angeles County. In March 2023, the court ruled that Hubbart was eligible for conditional release and the search process for his home began by housing contractor Liberty Healthcare DSH.

A representative of DSH stated that the court that “decided that the individual designated as SVP can be placed in outpatient treatment.”

Liberty found a place in Juniper Hills, which Judge Harrison said will take great care in considering, as if living in the area.

Juniper Hills resident Diane Swick, 60, transitioned from joy to despondency quickly in early August.

The retired dental specialist received a pacemaker in July to treat heart failure that left him with fatigue and difficulty breathing for months.

Two weeks into her new lease, Swick said she heard about Hubbart and sat in the house for a week, fearing that Hubbart might move to the nearby property within 300 feet.

“I wasn’t depressed, but I couldn’t move, I was so scared,” Swick said. “I don’t want to do anything and I feel like my world, my life is controlled by other people.”

Like Farrow, Swick raised horses along with various animals. What he likes most about the local community is its safety and security.

“I can leave the back door unlocked and not worry about someone breaking in,” he said. “I can leave my car unlocked and not worry.”

He sat in court confused as to why upscale communities such as La Crescenta succeeded in blocking Grassmier’s placement in 2021 but “AV was ignored.”

“Sometimes I wish the court could see what would be dangerous here and I wish Liberty Healthcare would actually consider it,” he said. “This is a community recovering from wildfires — especially the Bobcat fire — and this is a blow.”

Swick, however, continued to fight. He and his friends sent letters to Harrison while raising community awareness through social media and town meetings.

“What can we do but talk and let people know we’re here?” Swick said. “We are not sad. We are determined.”

Campa is a staff writer and House is a staff photographer.