The events that led these three climbers to the bosom of Annapurna in April 2023 were as different as they could be, but they did have one thing in common: all three of them had been declared dead on different mountains.

There are 14 mountains in the world higher than 8,000 metres above sea level. While Mount Everest is the highest, it is not the deadliest. That badge belongs to Mount Annapurna, where one out of every three climbers never come back.

Both Anurag and Baljeet were declared dead here. The mammoth was the first 8,000 metre peak for Anurag, while Baljeet was attempting to make the climb without supplemental oxygen, an extremely difficult and dangerous endeavour. As for Arjun, he’d already beaten death years ago.

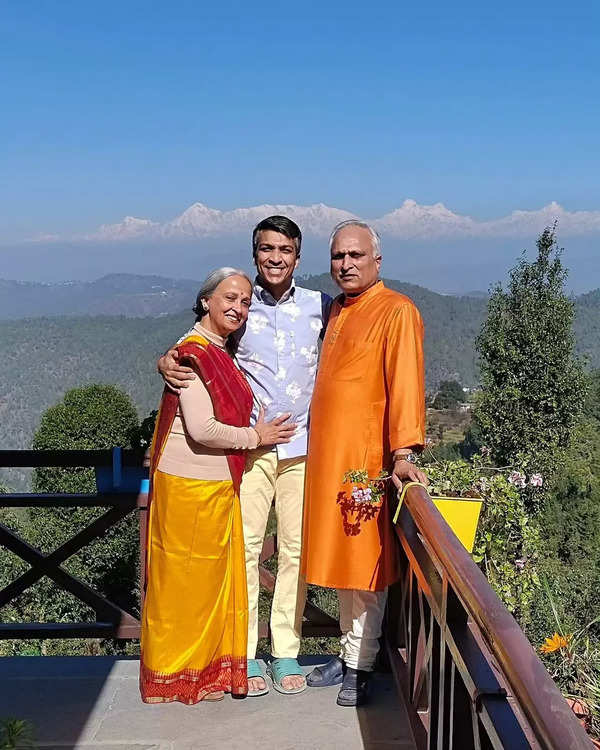

An unlikely climber from Noida

There would be few Indian mountaineers who haven’t heard of Arjun Vajpai. He was the youngest Indian to summit the highest peak in the world in 2010 at 16 years old, and more recently, he became the first Indian to summit Mount Shishapangma — the 14th highest peak in the world — in October, 2024.

Growing up in Noida, he wasn’t very different from other middle-class children his age. His father was an army officer, while his mother was an artist. “I’ve always been very passionate towards the outdoors,” says Arjun. “I was never a very good student, and I knew if I had to do something in my life, it had to be with my two hands and my two legs. As my sister put it, I have fewer brain cells,” he chuckles.

Arjun tried his limbs at several sports in school. He played football, basketball, did karate and even taekwondo. But as luck would have it, he didn’t start training when he was young and soon lost touch. What he did do from an early age was visit his grandparents in Pune. He was 10 years old when his grandfather took him for a hike to the Hanuman Tekdi hill.

“I reached the top of this hill in the evening with him, and we saw the sunset. I told my grandfather, “If it looks so beautiful from here, I want to see how beautiful it will look from the highest point on planet Earth.” He asked me, “Do you even know what’s the highest point on planet Earth?” I didn’t know. He told me it was Mount Everest,” Arjun recalls.

It seemed as though the gargantuan wheels of destiny had started chugging for him. When Arjun returned to school after his summer vacation, he found a chapter in his Hindi textbook titled: Everest Meri Shikhar Yatra (My journey to the Everest summit) by Bachendri Pal, the first Indian woman to summit Everest.

“By the end of the chapter, my Hindi teacher asked the class, “So, who all want to go climb Everest now?” I wasn’t surprised when I was the only monkey in the class with his hand up,” he says.

Life went on as usual for Arjun for the next four years with the only climbing he did was on trees to recover rogue footballs. In class 10, he decided to do a basic mountaineering course at the Nehru Institute of Mountaineering (NIM) in Uttarkashi.

He was 15 years old when he summited his first peak, Draupadi Ka Danda II (DKD – II), just shy of 6,000 metres. “I distinctly remember thinking I’ll never come back to the mountains again because I was so underprepared.” But just a month after he returned, he was already itching to feel the breathlessness in his lungs again.

The pahadi woman who trained at Siachen

Baljeet Kaur grew up in a small village in the Solan district of Himachal Pradesh. Although she lived in the mountains, mountaineering wasn’t something she had heard of growing up. That changed in 2015 when she went to college in Solan and joined the National Cadet Corps (NCC), the youth wing of the Indian armed forces.

“I was a naive kid from a village who’d never heard of fancy words like mountaineering until then,” she tells TOI+. “I couldn’t even say the word. I used to call it ‘mountaining.’”

Right from the get go, Baljeet was training with the Indian army. At first, she found climbing very easy. Her childhood experiences of carrying heavy loads up high altitudes weren’t too different from the basic skills of mountaineering. But it was when she advanced in her training and began climbing on snow and ice that she realised how tough the sport really is.

Baljeet’s first expedition was to Mount Deo Tibba, at 6,000 m. She climbed with 40 girls, of which 35 reached the summit. A few days before the expedition, it was snowing heavily. The girls — of all different faiths — prayed together for good weather. “That’s when I understood that humanity was greater than all faiths combined,” she says.

She was one of 10 women selected to train at Siachen for an expedition to Everest. They were taught how to climb, how to rescue, how to get out of a crevasse, and all the ins and outs of mountaineering. There were no helpers and no sherpas, they were taught to be self-sufficient.

In 2016, she went on her first expedition to Everest, but failed to summit. Her oxygen mask had stopped working and she had to turn around just 300 m below the summit. “It was good that I didn’t summit,” she says. She was told that if she summited Everest, the government would pay for her education and give her a job. All she wanted was for Everest to be the means for her to get an education. She soon realised she was climbing for the wrong reasons.

The next year, she did another advanced mountaineering course but didn’t climb for another three years.

In 2019, she joined an Indian Mountaineering Foundation expedition to Pumori. This was the first time she was climbing with men. “By that time, I was so desperate for mountaineering that I no longer needed Everest. I just needed a mountain to climb,” she recalls.

She read about Mount Pumori and learnt that it was called Everest’s Daughter. She thought, “Okay, I couldn’t meet Everest but I can meet her daughter.”

In 2021, she was part of the first Indian group to summit Pumori, and became the first Indian woman to stand atop the peak. “I have never spoken of the other people who summited with me, but I’ll tell you their names today. There was Stanzin Norboo from Ladakh, Hem Raj, and Gunbala Sharma from Rajasthan,” she reveals.

She climbed the 7,000 m high Mount Kun next before embarking on her 8,000 m journey the same year. Baljeet’s first of the 14 highest peaks was Dhaulagiri, the seventh tallest mountain in the world. She only had a one-day window of clear weather, and became the first Indian woman to climb Dhaulagiri.

A teacher with tall dreams

Anurag Maloo grew up in Rajasthan, far from any ice-clad mountain peaks. He went to college in Delhi and only learnt about mountaineering after graduating as a software engineer in 2011. He knew pursuing this new-found passion was not feasible for him since he had already signed up for a fellowship with Teach for India.

Mountaineering is an expensive sport and Anurag knew he couldn’t ask his family to pay for it. He had no choice but to get to work, build himself a career, and save up enough money to one day be able to support this dream. “The expectation was that I was going to support my family as a software engineer but I’d already made an odd decision of teaching children from disadvantaged backgrounds,” he says.

But he did have some experience with mountains before he formally decided to pursue the sport in 2020. Anurag was posted in Pune as a Teach for India fellow and spent his weekends hiking up the hills of the Sahyadris. His other passion was teaching his students about sustainability. When he met his idol Robert Swan — an explorer who walked to both the North and South poles — in Pune by chance, he got the opportunity to accompany him to Antarctica in 2013 to “talk about the role of teachers in bringing sustainability into classrooms and schools.”

Anurag was in Antarctica for two weeks, which truly cemented his love for mountains. The expedition ended, as did his fellowship, and Anurag dove right into a job with a venture capital and investment firm helping start ups. “I was probably travelling every week to a different country,” he says. He got so busy in his day-to-day life that he forgot that he ever had a different dream.

That was, until Covid hit in 2020. He went for a leadership summit to Sri Lanka and wrote about where he saw himself in 5-10 years. “I see myself climbing these mountains by 2025,” he remembers writing. By the time he returned, all travel had stopped. So, Anurag started running. “I became comfortable with running five kilometres everyday. Eventually, 10 kilometres,” he says.

In October that year, he got the opportunity to go for a three week expedition going from Uttarakhand to Himachal Pradesh through high-altitude mountain passes. “That’s when I realised, this is the time I have been waiting for all my life,” he recalls. “If not now, when will I prioritise my mountaineering? That old dream I had since 2011?”

By the end of that expedition, he told Bachendri Pal, “I have a dream of climbing Everest without oxygen.” She told him he would need a very different kind of training for that and recommended he do a mountaineering course. He took her advice, but not before climbing two more 6,000 m peaks in Ladakh. Then, he enrolled himself for a basic mountaineering course at NIM.

The 8,000 metre journey

The first 8,000 m peak Arjun climbed was Mount Everest, and he made it to the summit on his first attempt. But it took a village to send him there.

When Arjun told his parents he wanted to climb Everest, his father made a few phone calls to his former colleagues in the army. They found out that an expedition to Everest costs upward of Rs 35 lakh. Arjun’s family didn’t have that kind of money, so he took matters into his own hands.

A journalist had visited his school to speak to the academic toppers when Arjun was standing outside his principal’s office holding a summit picture from DKD – II in an attempt to explain his absence. He’d taken his school flag along with him to the top of the mountain to help soften the blow.

The journalist saw the photograph Arjun was holding and reported on his achievement. At the end of the article, Arjun mentioned he wanted to climb Everest. “A 16-year-old climbing the world’s highest mountain…it had never been done before,” says Arjun.

Some 24,000-odd people believed in his dream and started sending him money for the expedition. “There were carpenters, government school teachers, ladies sending Rs 500 from their pensions, these were people who had never met me,” he recalls. “They believed ‘if Arjun can make it to the top, we’ll also make it to the top with him.’”

Eventually, his father filled in the remaining Rs 5 lakh and Arjun was on his way to the top of the world. “I became the youngest person in the world to climb Mount Everest,” he exclaims. “For the first time in my life I could see that the Earth is round. You’re looking down at the sun when it is rising. For the first time in my life I saw light travel.”

When he returned to base camp, some elite mountaineers told him about the 14 peaks higher than 8,000 m and the 32 people (back then) who had climbed them all. When Arjun came back home to Noida, he looked up these 32 people online. There was no Indian on the list. “So that day I dreamed that I wanted to put India in this list of elite climbers.”

In 2011, he climbed both Lhotse and Manaslu in his first attempt. “I felt like Hercules,” he says.

The next year, Arjun met the mountain that killed him.

Five peaks in one month

Although Baljeet had gotten away with climbing without sponsors so far, she suddenly found herself needing them to continue her 8,000 m journey. When she approached different companies for sponsorships, they cursed at her and turned her away, she says.

“I struggled to get sponsors. I just wanted one chance and I would show the world that I’m the right person to bet on. I’m here for India,” she recalls. Indian mountaineers had a bad rep and both sherpas and international climbers felt they were underprepared, lazy and slow, she explains. Both Baljeet and Arjun wanted to change this perception.

In 2022, Baljeet climbed five 8,000 m peaks back to back in 30 days — Annapurna on April 28, Kangchenjunga on May 12, Everest on May 21, Lhotse on May 22, and Makalu on May 28.

Whatever money she had saved up to build a house, she spent it on the Annapurna expedition. She also didn’t have a manager or a team to coordinate with sponsors during her climb. She texted sponsors whenever she had some mobile network and had to figure out her permits all on her own. In fact, by the end of her five summits, she’d spent Rs 86 lakh and was Rs 48 lakh in debt. Several sponsors, who had initially agreed to pay, disappeared after her summits.

Little did she know, she’d met her guardian angel on her way back from Kangchenjunga. One day, she found a middle-aged woman from Mumbai there who wasn’t getting along with her sherpa. The woman didn’t speak any Nepali and the miscommunication led to an argument between the two. That’s when Baljeet stepped in. She helped mediate the situation with whatever little Nepali she knew.

The woman was grateful for Baljeet and told her, “If you’re ever stuck, give me a call,” and shared her phone number. Baljeet didn’t think much of it. She’d met many people during her travels who wove tall tales of how they could help her but never really came through when she needed them.

“The climbs weren’t difficult for me, what was difficult was managing all the sponsors and logistics,” she recalls.

So, here was Baljeet struggling with debt after climbing five of the world’s highest peaks, when suddenly, she got a call from the same woman, Amisha Vora, chairperson and MD at Prabhudas Lilladher, a stock broking company. She gave Baljeet Rs 35 lakh as sponsorship.

“I felt like god was testing me,” she says.

Life came full circle when she met with a pharmaceutical company’s MD for sponsorship. A man entered the room and told her, “You don’t remember me, but I had once kicked you out of my office. I’m sorry.”

Navigating through setbacks

Anurag says he is an experiential learner and learnt more while climbing peaks with experienced climbers than in a classroom. After climbing several 5,000 m and 6,000 m peaks, Anurag decided to climb Mount Satopanth in Uttarakhand, a 7,000 m mountain. He had to turn back before reaching the summit because his instructor felt he showed symptoms of acute mountain sickness.

He was heartbroken. “My confidence, my motivation, I just lost it,” he recalls. “I was so depressed.” But after speaking to a few friends and Bachendri Pal, he realised that these setbacks were a part of his mountaineering journey. He was determined to see this through and decided to climb Mount Nun (7,135 m) in Ladakh along with Baljeet. The same year, he climbed several other mountains — including Mount Ama Dablam, widely known as the Matterhorn of the Himalayas — until he felt ready to tackle the 8,000 m peaks.

Death on Cho Oyu

Cho Oyu, the sixth highest peak in the world, is considered one of the easier 8,000 m mountains. Arjun was attempting to climb both Cho Oyu and Shishapangma in one season in the autumn of 2012.

By the time he reached Camp II at Cho Oyu, the weather reports showed severe winds, as did the mountain above him. But in his mind, Arjun was already trying to reach Shishapangma. So, he hurried. “Nature does not know the difference between a big mistake or a small mistake, it’s a great equaliser when it comes to consequences,” he says.

There were hardly any teams attempting to climb Cho Oyu at the time, and Arjun was making the ascent with two sherpas. They were struck by a snowstorm at 7,100 m and were stuck up there for four days. On the fourth morning, Arjun woke up drooling and unable to feel his left arm. He shook his sherpa awake, who immediately knew something was wrong.

The 18-year-old had developed 11 blood clots on the right side of his brain and was partially paralysed. Both the sherpas burnt through their entire butane supply — which is the only gas that burns in high altitudes — to warm him up, hoping to reverse the paralysis.

Then the younger sherpa fell ill. Both the sherpas had accompanied Arjun to Everest, Lhotse and Manaslu. They had met each others’ families. And while Arjun was on the mountain chasing adventure, for the sherpas, it was their livelihood. So, Arjun asked them to leave and return for him when the storm subsided.

“I had been in previous expeditions where we had to leave people behind to come back with a mightier force. But this time I was the one being left behind and it was definitely not a good feeling,” he recalls.

Arjun called his mother with the little bit of battery he had left on his phone and told her that this time he might not return. His mother had a panic attack and his father, otherwise a stoic military man, broke down for the first time in front of him. “At least try to move. Don’t give up, try and move,” his father pleaded.

After the call, he was left alone with his thoughts, drowning in his bodily fluids. Arjun knew that death was fast approaching.

The next morning, as Arjun looked outside his tent, he saw the storm had uncovered the petrified body of a dead climber nearby. It made him think about how he wanted to be found. “What if people find me dead inside the tent and think that I gave up? My father’s words were ringing in my ears,” he remembers.

Arjun ripped the tent apart with his crampons and began dragging his half paralysed body across the snow. He followed the sloping mountain for a few hours until he reached an ice cliff. Normally, a climber would rappel down this 130-metre wall of ice, but Arjun couldn’t. He looked down the cliff as he was slowly getting covered by snow.

“If I’m going to die on top of this cliff, I might as well die at the bottom of the cliff,” he thought with a chuckle while retelling the story to TOI+.

He jumped and came tumbling down.

“That is the moment I felt life escape my body, my soul escape my body,” he says.

Unbeknownst to him, the storm cleared up quickly after that. A rescue team came up the mountain looking for him and found his body just a few hundred metres away from Camp I. He had apparently crawled for hours after the fall but had no recollection of it.

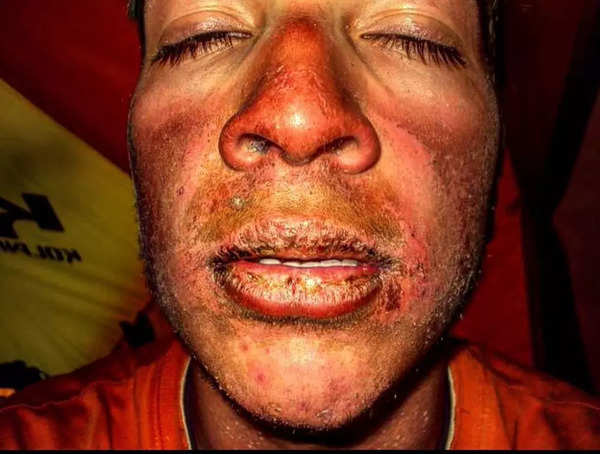

“They took a picture. There was no pulse, there was no brain activity. They pronounced me dead, noted the time of death, put me in a sleeping bag, tied me to a mattress and started bringing me down,” he says.

As they were bringing his body down to basecamp over a patch of loose rocks, Arjun’s heart started beating again. “The storm had ended, they had descended in altitude, I was in my suit inside a sleeping bag, so I think I became warm and came back to life,” he laughs. “I’m literally like a cockroach.”

He shook inside the sleeping bag, terrifying the sherpas carrying him. They thought it was a ghost. They dropped the ropes and Arjun’s body went crashing down the scree. He banged his head against the rocks and groaned in pain inside the sleeping bag.

The sherpas quickly opened the sleeping bag and pulled him out exclaiming, “Oh! He’s still alive!”

Once back in India, Arjun was admitted to AIIMS and was paralysed for six months. He was on heavy steroids, which turned his hair grey, but constantly fought the doctors who wanted to amputate his paralysed limbs. “One fine day, I woke up and my left leg started to move.” He still has the blood clots in his brain.

Climbing without oxygen

In 2022, even after summiting five peaks in a month, Baljeet wasn’t done. In fact, she decided to up the ante and climb without supplemental oxygen. “I became the first and youngest Indian woman to climb Mount Manaslu without oxygen,” she recalls.

But it wasn’t an easy climb by any means. Baljeet and her guide were hit by an avalanche during her ascent and were declared missing for a few hours. Since Baljeet’s sherpa had thrown his backpack with the walkie talkie when he saw the avalanche approaching, they couldn’t inform anyone of their whereabouts. Several people were injured and the duo started rescuing them.

Baljeet had dug out one of the injured climbers and was trying to resuscitate him when he died in her arms. That broke her spirit. “Why are we in the mountains? I don’t want to do this anymore,” she recalls thinking. But her guide motivated her to keep moving forward.

Later that night, she thought about it. “This is what we’re in this world for, right?” She thought. “We all have to die one day, so it’s better to die without any regrets.”

She got back up and started climbing. And summited Manaslu without oxygen.

Then, she trained her gaze back at Annapurna, a more technical mountain to climb without oxygen.

Choosing Annapurna

Anurag didn’t pick Annapurna to be his first 8,000 m mountain right off the bat, he was considering other peaks as well. “I was thinking, ‘Why did I want to climb these mountains?’ And it became very clear to me that if I am to start climbing the 8,000 m peaks, I want to start with the most difficult mountain,” he says. “The logic was simple: if I can climb Annapurna, then I can climb any other mountain in the world.”

He also felt a special connection to Annapurna. He saw the mountain as ‘Maa Annapurna’. “I will start with Annapurna, then I will climb Everest, Lhotse and Makalu,” he recalls.

Anurag had planned to climb four peaks in the spring of 2023. As a working professional, he didn’t get unlimited leaves. “It’s not like I was on holiday. When I was on the mountain without internet, I was on holiday. Otherwise I was working remotely, earning and supporting my expeditions,” he adds. Anurag didn’t have any sponsors and paid for each expedition out of pocket.

But this wasn’t just a well thought-out plan for him. He had a deeper connection with Mount Annapurna: it reminded him of his grandmother. “I used to climb mountains for two reasons. I used to climb to promote the sustainable development goals as well as for my grandmother,” he explains. “My grandmother passed away a few years ago, but even before that, I used to take my grandmother’s photograph with me during my expeditions.”

“I can’t explain my relationship with my grandmother. It was magical. I was my grandma’s favourite and she was mine.”

He said never felt anything bad was going to happen to him in the mountains because he felt so loved. “Whatever name you want to give that — mountain, or Maa Annapurna, or my grandma Saraswati Devi, or mother nature — for me, it was all the same. And she’s always been there protecting me,” he says.

A deadly season

By the time Arjun reached Annapurna in April 2023, he had also summitted Makalu (on his fourth attempt), Cho Oyu — he went back in 2016 and that’s when he regained his memory of the chain of events that transpired five years back — and Kangchenjunga. He had attempted Annapurna twice before but had been unsuccessful.

On his third attempt on the mountain, Arjun stayed back at base camp waiting for the weather to clear, while a large group of climbers went for the summit push. “It was blatantly told to me by my senior mountaineers that Annapurna is not a mountain for amateurs.” So, he didn’t want to take any chances.

When he reached Camp IV, other mountaineers — including Anurag — were on their way down. Baljeet had stayed back at Camp III since she was attempting Annapurna without oxygen this time.

Arjun’s group of climbers made it to the summit and he lost his phone immediately after when it fell out of his suit. He said they had already summited very late in the day and his fellow climber Noel Hanna was struggling with a bad cough. On the way down, he met Baljeet who was making her ascent. “Baljeet is one of the strongest Indian mountaineers that I’ve seen,” he says.

By the time he reached back down to Camp IV, a storm had started at the summit. Usually, it’s easy to see other mountaineers going up the mountain in the snow, but they were no longer visible to Arjun. But things were not right at Camp IV. There was no food, no water, and no butane. All of their rations had been exhausted by previous climbers.

At around 5 pm, they heard a sherpa cry out on the radio, “Anurag’s fallen! Anurag’s fallen!”

Two Polish climbers who had summited just 15 minutes before Arjun were on their way down at the time. They gave Arjun’s group a can of butane before rushing down to answer the distress calls on the radio, Arjun said.

By nightfall, Anurag was still in the crevasse. Arjun, who was exhausted in his tent, saw two sherpas come running down yelling, “Baljeet is lost! Baljeet is lost!” He said they no longer had the energy to even stand up straight, let alone go on a rescue mission.

The next morning, Arjun woke up to a new tragedy. Noel Hanna had died in the tent next to him due to the lack of oxygen, water and food, he says. “I can say it’s because of all this but when your time arrives on the mountain, even the people with the most resources and experience are not able to make it,” he adds grimly. Arjun didn’t want to leave Noel’s body in the mountain so he stayed back to help get the body down by helicopter.

Hallucinating on the summit

Baljeet, who was climbing without oxygen, found herself without the team she had signed up for. Her sherpa had left for Kathmandu just days ago without explanation and she was on the ascent with a guide who hadn’t had enough time to acclimatise. He’d fallen ill at basecamp, so Baljeet decided to delay her ascent by a day.

On the day of her summit push, the sherpa sent Baljeet ahead with a porter and said he would join them in a few hours. But the sherpa who met her later was one who had summited with her friend earlier that day. He, however, did not have experience with climbers without oxygen, she says. “He had also not rested after his previous summit.”

Baljeet started her summit push at around 1 pm on April 16, but couldn’t reach the summit even by 5 pm the next day. She was just 50 m below the summit when she told her sherpas, “It’s too late, let’s go back.” She knew that something was wrong.

The sherpas encouraged her to keep going since they were so close to the peak. “It wasn’t their fault. They had oxygen so they couldn’t feel what I was feeling,” she explains. “They also didn’t know what all could happen while climbing without oxygen, and they also wanted to summit for professional reasons.”

Baljeet remembered the reputation of Indian climbers that she was trying to break and decided to keep going. It was only her second climb without oxygen and her sherpas didn’t know to keep telling her to hydrate herself throughout the climb. Just 20 m from the summit, she had her first hallucination.

Baljeet had forgotten to carry the Indian tricolour and she saw a young girl on the mountain selling a flag. “You take this flag to the summit,” the girl said. But when Baljeet reached out to pay her, the girl disappeared.

She told her sherpas that she wanted to turn back. She clicked some photographs, and recorded a video apologising to her sponsors for not reaching the summit. But then she saw her sherpas had started climbing towards the summit. Still hallucinating, Baljeet thought they were leaving her on the mountain and started following them. Soon, she reached the summit.

On her way back down, she saw a bamboo forest all around her and someone was calling her name, “Baljeet? Baljeet!” A couple of her friends were sitting inside a tent, calling her. “Come inside the tent, Baljeet. We’ll give you hot water and a sleeping bag.” She told her sherpas, “Come, let’s sleep in this tent. My friends have sleeping bags, let’s sleep here.” None of it was real.

The sherpas were also out of oxygen by that time and realised that Baljeet could no longer walk on her own. They told her to walk faster or they’d leave her. She walked for a bit but soon collapsed on the ground. Baljeet was breathless.

One of the sherpas said, “Baljeet, we don’t want to die because of you.” This statement took her back to the incident at Manaslu when a climber had died in her arms. Baljeet told the sherpas to leave without her.

The entire night Baljeet was in and out of sleep, ricocheting between hallucinations and lucid thoughts. She dragged herself down the slope whenever she could while the voices in her head got louder. She woke up the next morning and realised she was still on the mountain. She could hear local Punjabi, Bengali, Gujarati music in her ears. At one point, the music and chatter got so loud that she yelled, “Stop! You’re making too much noise!” That snapped her back to reality for a bit and she made her way back down.

At one point, she jumped off a steep slope and thought she forgot to anchor herself to the rope. “I felt like this was it, I was going to die,” she recalls. But suddenly she felt a jerk and her fall was broken. She had, in fact, anchored herself to the rope. The voices in her head got louder. They told her to remove the safety anchor and jump. But then she heard a familiar voice, it was one of her old instructors saying, “What are you doing? This is your lifeline.”

In and out of hallucinations, Baljeet spent the next day lost on the mountain top. She could see helicopters flying overhead, rescuing other people, but it didn’t occur to her to call for a rescue herself until she accidentally glanced at her iPhone. She pulled it out of her pocket and sent a message to her agency through the satellite app: I’m here alone, I need rescue.

Back at basecamp, news had spread that Baljeet was dead. But when the agency received her message, they realised she might still be alive. “They thought it was a message from the previous day, which was delivered late,” she says. They texted her back and realised she was definitely alive. “Then all the articles published about my death were deleted and updated,” she laughs.

Because Baljeet was still hallucinating, the rescue was complicated. In her fraught state, she had to remind herself to not say ‘no’ to the rescue when the chopper arrived, remove her safety anchor from the rope, anchor herself to the chopper’s rope and climb up.

Thankfully, it all went as planned and she was rescued off the mountain on the afternoon of April 18.

The great rescue

Anurag’s summit push didn’t go as planned either. His ascent was slow as he was struggling with his glasses fogging up due to the oxygen mask, so he had to keep removing it. He was 150 m away from the summit in the afternoon but the weather was quickly changing. “It would have taken me 2-3 hours to summit because you are in the death zone,” he explains. “Every step is so heavy.”

He spoke to his sherpa and realised that if he continued, he might have reached the summit, but wouldn’t have been able to come back at night. He decided to turn back and make another summit attempt in a few days when the weather was better. On the way down from Camp IV, he bumped into Baljeet who was on her way up.

The next day, while descending from Camp III to Camp II — one of the most dangerous, avalanche-prone areas of the mountain — tragedy struck. “I have no recollection of that time. All I learnt is that I picked the wrong rope by mistake. That rope shouldn’t have been there on the mountain, it was a broken rope,” he recalls. “I had a big fall. The agency said a 250-300 m fall. And then I entered the mouth of a crevasse, some 70-80 m inside the earth.” And that’s where he was trapped for three days and three nights.

While several people tried to rescue him, the weather along with inadequate ropes made the rescue impossible. He learnt later that everyone thought his chances of survival were bleak.

Anurag says that mountaineers are the first to give up since they know the reality of the mountains. Soon, he was declared dead in newspapers and magazines as well.

When Polish climbers Adam Bielecki and Mariusz Hatala reached the basecamp after their own expedition, they were asked by Anurag’s agency if they knew how to carry out such a rescue. Anurag says they agreed to descend down to a crevasse to bring back what everyone thought would be his dead body. They allegedly said, “This is what we would expect from others when we are in a similar situation: that people would come and help us as well. If we won’t, who else will?”

Anurag’s friends and family back home in India had mobilised themselves to push authorities in both India and Nepal to facilitate his rescue. “It was a body recovery mission that turned into a rescue mission when they saw me alive.”

Bielecki had rappelled down 70 m, kicked Anurag, and saw that he was still breathing. He was airlifted out of Annapurna to a hospital in Pokhara. After 30 minutes of CPR, they too declared him dead. But his younger brother Ashish, cousin Sudhir, and uncle Gopal kept pushing the doctors to keep doing CPR. They had a hunch he was still alive. “After four hours, I took my first breath,” says Anurag. He was then flown to Kathmandu, where he was in a coma for some time. After 21 days he was stable enough to be flown back to India and admitted to AIIMS for his reconstructive surgeries.

Anurag’s last memory on Annapurna was just before the fall, and his first memory after the rescue was when nurses in Kathmandu were dressing his wounds. He still didn’t know what exactly had happened to him until July 2023, when he pieced the chain of events together through family anecdotes, news reports and talking to people.

Surprisingly, there were no avalanches during the three days he spent in the crevasse, except one that buried him in snow the night before his rescue. When asked if he will climb again, “I don’t decide that,” he says. “I think the mountains will decide. If I should be there again, there will be a call from the mountain and I’ll follow.”

Anurag walked away from the experience calling it a blessing. “It’s a blessing that Annapurna chose me over anyone else. It took care of me, protected me,” he explains. “The mountain that’s known for taking people’s lives has given me my life back.”