Guest Essay by Kip Hansen

In the “make climate a part of every beat in the newsroom” mainstream media, we get stories like this in the NY Times tthis week: “To Save More Water, American Homes Need Smaller Pipes — Most of the plumbing pipes in the United States are oversize, wasting water in a time of increasing drought.” authored by Megy Karydes.

The piece is absolutely hilarious — the NY Times journalist somehow arrived at a very wrong interpretation of something that was explained to her:

“Oversize plumbing pipes move water inefficiently, wasting money and increasing the risk of waterborne diseases. And water efficiency is especially important as climate change makes droughts more frequent and severe.”

Ten points to the first few readers to spot the gross misunderstanding.

She goes on: “When the current method for sizing pipes to transport hot and cold water throughout the home was created in the 1940s, it was under the assumption that every fixture had to be able to support a line of people for the bathroom, like at a sports stadium at halftime, according to Christoph Lohr, a mechanical engineer specializing in plumbing systems and the vice president of technical services and research for the International Association of Plumbing and Mechanical Officials, a trade organization.” …. “But even during a party at home, there won’t be a line for the kitchen sink, the shower, the bathtub, the laundry machine, the dishwasher and the toilets, with people using them over and over. In other words, most plumbing fixtures in the United States are designed to accommodate total flow rates far higher than they will realistically encounter.”

Really? How did a matter of plumbing size get assigned to someone who must not even have a high school understanding about fluid flow or home plumbing system design?

Number One: Larger than necessary pipes do move water less efficiently – takes more energy to move the water through too-large pipes – and too large pipes, which don’t get a lot of throughput, can develop biofilms that can be the source of some illnesses.

Number Two: Number One has nothing to do with the concept of “water efficiency” that is related to total water usage and thus peripherally related to drought.

In case Megy Karydes reads here, I will explain: The stadium example mentioned by Mr. Lohr has to do with the number of sinks, urinals, and toilets expected to be in use simultaneously, which requires a high volume water flow … the number of people waiting in line, does not affect flow of water at all (ever). In the journalist’s home, there may well be many people needing to use the sink or toilet but not at the same time…just one after another, which does not affect required water flow or affect choice of water supply line pipe size. Larger supply lines or larger pipes do not use more water (except to fill them initially) – water use as water volume depends on the outlet size and time the water is allowed to flow – in our modern US homes this is regulated by flow restricting washers, which are placed in the faucets and showerheads, with differing sized holes.

(Note: To clarify, flow is the amount of water moving through the pipe and out the faucet. Total water use is the volume of water used. Larger flows require larger pipes – just like fire hoses come in several sizes. But this does not apply to normal home water use. Water pressure also is part of the equation of water use – higher pressure through the same sized outlet increases water coming out of it .)

I bet you all already knew that, but it had to be said.

The size of pipes used in household plumbing does not affect water usage at all. (There might be a tiny itys-bitsy effect when the house water system is first filled, but that is all, a few extra gallons of water stored in the pipes, but this is not ongoing use.)

Household water use is determined by the length of time water is flowing and at what rate it flows through the system. Saving water is done installing:

1. Flow restricting faucets (either factory restricted or by the addition of flow restricting washers). Usually 2.2 gpm or 1.5 gpm (gallons per minute).

2. Flow restricting shower heads. EPA’s WaterSense standard is no more than 2.0 gpm.

3. Low-flush toilets. Current standard 1.6 gpf (gallons per flush) for solids and 1.1 gpf for liquids. EPA WaterSense high efficiency certified toilets use 1.28 gpf.

( reference for these )

4. Water-saving appliances: washing machines and dishwashers.

5. Laws and regulations on landscape watering.

A bit of Home Plumbing 101:

A water service line comes from the water main to the house. The size of the water service line determines the maximum total water flow/volume (at normal water pressure) that will be available in the home. In my county, the minimum size of the water service line is ¾ inch. All new single-family homes here have ¾ inch supply lines while those with more than one living unit have 1 inch service lines because they will need more total water flow.

A water supply line means the pipe from the incoming water source to a water use point – like a bathroom. In the diagram above, the supply lines are blue for cold water and red for hot water. The hot water heating system has incoming cold water supply and outgoing hot water supply lines. There are T’s in supply lines that divide up the supply of water, sometimes through smaller pipes, and send it to the sinks, appliances, bathtub faucets, shower-heads and the toilets.

Personal Note: In my home, when I had a single upstairs bathroom remodeled into two smaller bathrooms – one with a tub and the other with a shower stall – I had to specify supply line size to my plumber. He wanted to use less expensive ½ inch copper pipe (this is before modern PEX piping). I specified ¾ inch supply for the hot water – as the supply line would feed two bathrooms for six people, three of which were teenagers, and a supper-sized hot water tank, as both showers were likely to be in use simultaneously every morning and evening.

Well, now, we have seen that home plumbing water pipe size does not contribute to “wasting water in a time of increasing drought.”

Wait! What does this have to do with droughts?

Nothing whatever. As in, nothing at all.

But are we “in a time of increasing drought”?

Not according to the IPCC. In AR6, Chapter 12, Table 12.12:

The IPCC’s latest estimate of the predicted time of emergence of various Climatic Impact-drivers (CIDs) – “‘Time of Emergence’ refers to the time when anthropogenic change signals emerge from the background noise of natural variability in a pre-defined reference period” — shows that no signal Hydrological Drought or Agricultural and Ecological Drought has yet emerged. Not only not happening in present time, but not expected to be seen by 2050 and not expected to emerge between 2050 and 2100. Despite what the mainstream seems to say every day, in simple language, increased and more frequent drought is just not happening.

There are a lot of doubts and confusion about drought. In the United States, the primary source of confusion about droughts comes from the NOAA’s National Integrated Drought Information System through its website at Drought.gov.

Information from drought.gov ends up in the main stream media as this:

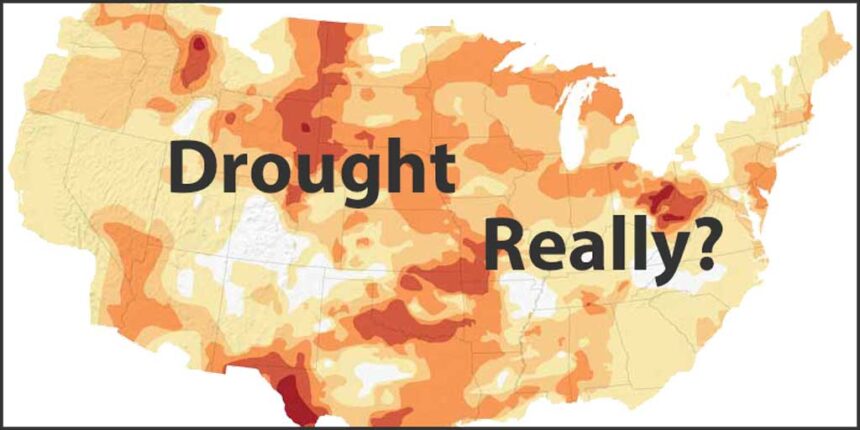

In a Record, All but Two U.S. States Are in Drought

Which uses drought.gov’s illustration:

I am not contesting the image or the data behind it. But I will state categorically that it is the specific type of mis-information that we see all through the weather and climate news: The actual meaning of the image (in this case) received by the pubic will not be the reality – there is not any context or clear plain language statement of what the image means for the public.

Definition: “A ‘plain language statement’ in science is a concise summary of a … scientific finding written in easily understandable language, designed to be accessible to the general public without requiring specialized scientific knowledge.”

Why is it that the primary source of doubt and confusion about drought is the very agency department whose primary responsibility is to track and inform the public about drought conditions in the United States?

It isn’t that they are trying to fool the public with mis-information. They are not bad actors trying to push “The Climate Crisis”. They do good science and report their results accurately.

If so, why the doubt and confusion?

According to the National Geographic:

“Drought is a complicated phenomenon, and can be hard to define. One difficulty is that drought means different things in different regions. A drought is defined depending on the average amount of precipitation that an area is accustomed to receiving.” … “A drought in Atlanta could be a very wet period in Phoenix, Arizona!”

There are at least 11 types of droughts mentioned at aginfo.in (unfortunately no longer active, but the link goes to the ever-helpful Wayback Machine – I send money every time I am forced to use them).

Dr. Jim Angel, State Climatologist of Illinois, says this:

“Drought is a complex physical and social phenomenon of widespread significance, and despite all the problems droughts have caused, drought has been difficult to define. There is no universally accepted definition because: 1) drought, unlike flood, is not a distinct event, and 2) drought is often the result of many complex factors acting on and interacting within the environment.

Complicating the problem of drought is the fact that drought often has neither a distinct start nor end. It is usually recognizable only after a period of time and, because a drought may be interrupted by short spells of one or more wet months, its termination is difficult to recognize.”

So, when the NY Times prints (on paper or digitally) the image used above, they surely explain that this is a representation of an “index” called “U.S. Drought Monitor”. Don’t they?

Well, no, they don’t explain that that is what we are looking at.

The “U.S. Drought Monitor” is an index about drought: “A drought index combines multiple drought indicators (e.g., precipitation, temperature, soil moisture) to depict drought conditions. For some products, like the U.S. Drought Monitor, authors combine their analysis of drought indicators with input from local observers. Other drought indices, like the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI), use an objective calculation to describe the severity, location, timing, and/or duration of drought.”

The U.S. Drought Monitor (index) is not an objective calculation about drought or it’s severity in any particular location….involving more than one measure plus “input from local observers”.

My home area is “in a drought condition” which had little or no effect for my family – other than we had to water the vegetable garden twice in a month – which is not different from non-drought conditions.

Here’s another look of the continental U.S. drought conditions produced the same week as the image above, for the month of October 2024, but using different indices:

While they are somewhat similar, they do not even duplicate the deep severe drought in southwest Texas and southern New Mexico. Comparing them side-by-side, or diagonally, often finds no similarity on a state or region basis. Two of the four indices show the Northeast US in fairly serious drought, while the other two show the Northeast to be wet (green and blues) which is the opposite of drought.

The US Drought Monitor drought index is a very subjective metric of drought – and mostly means “less rain over the period (week, month, year) than average”. What it does not mean is that local water companies have to start restricting water use or call for voluntary water usage.

However, lack of rainfall can and does affect some cities (megalopolises) that depend on rain-fed reservoirs for drinking water. New York city’s biggest reservoir is currently down to 60% of normal. It will fill back up when winter rains and snows arrive. In areas where large cities depend on water pumped from deep aquafers, long-lasting problems can develop as these deep aquafers take many years/decades to refill. This is not an effect of drought but rather an effect of over-withdrawal.

CONFUSED? I don’t blame you.

# # # # #

Author’s Comment:

While researching for this essay, I came across this statement at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA):

“When you use these water–saving products in your home or business, you can expect exceptional performance, savings on your water bills, and assurance that you are saving water for future generations.”

My home water supply used to come from one of two wells on our property, not exceptionally deep, but we never ran the well dry. Now we have “city water” that comes from a small dammed stream five miles away, the dam creates a small pond. The water not used by the water treatment plant there runs over the dam and then down the hills eventually into the Hudson River, which runs to the sea.

This setup is the same as it is for NY City, though NY has many distant reservoirs. But in the end, the water not used by NY City flows over or through the dams, down rivers into the Atlantic Ocean. All the waste water from NY City also flows into the Atlantic (albeit with a great deal of loss from leaking aquaducts).

No amount of saving water from these reservoirs benefits “future generations”.

Fresh water, where it is in low supply, can be wasted, used in foolish ways like to water desert golf courses. But only when this ssavings is of water pumped from aquifers does this saved water benefit our children and grandchildren.

Do you know where your water comes from?

Thanks for reading.

# # # # #

Related