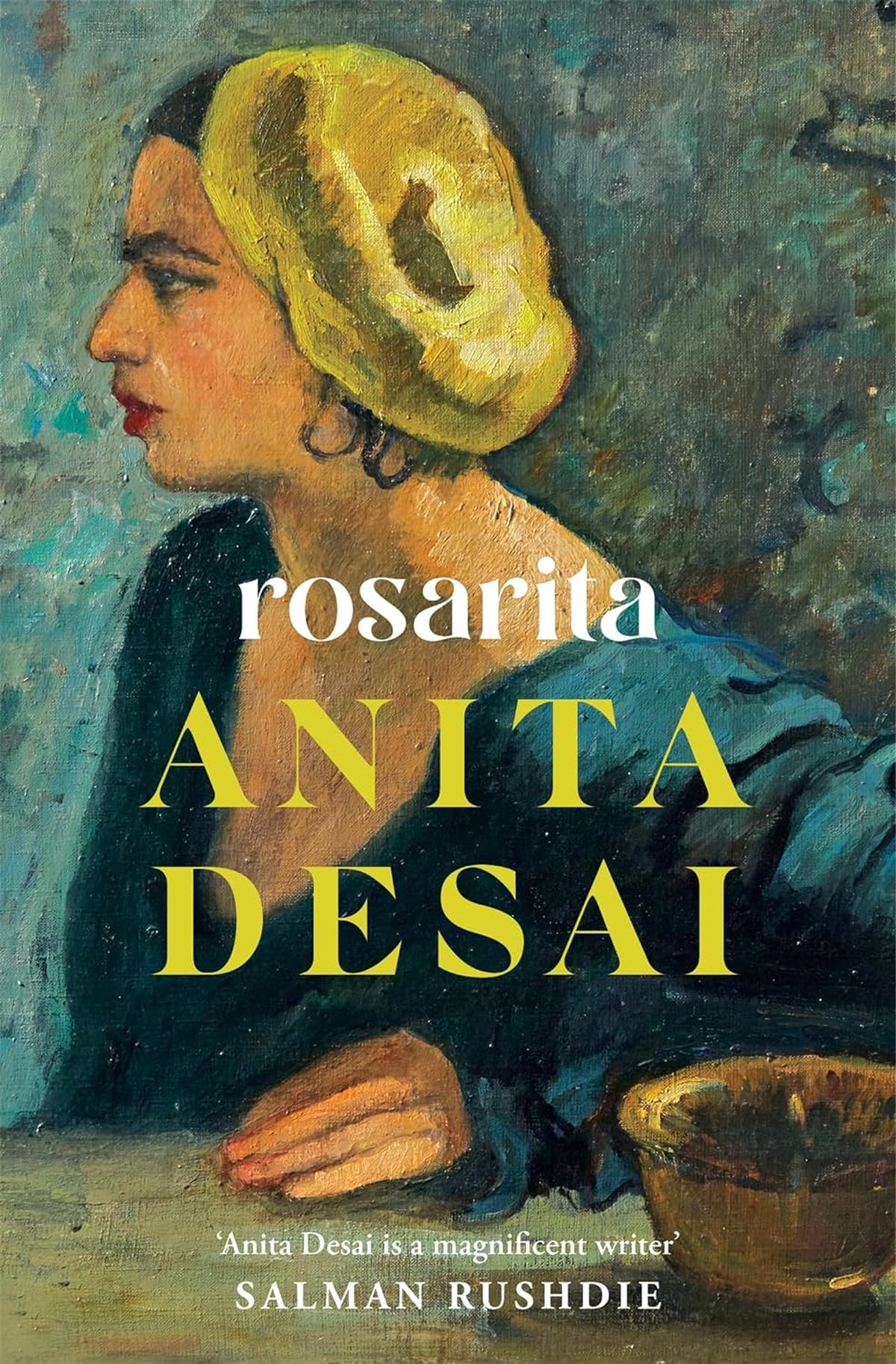

Anita Desai has often experimented with language, themes and forms in novels like this Clear Daylight, Fasting, Fasting, Baumgartner’s Bombay and The Vanishing Artist. In the end he Rosarita (Picador), a dreamlike novella, Desai gives the narrator another person’s voice. When a stranger plants the idea in the mind of the young student Bonita, that her mother’s name is Rosarita and that she has studied art in Mexico, he sends her imaginatively to fill the absence left by her mother. In a phone conversation, the soft-spoken and three-time Booker Desai, who is now 87, talks about his relationship with Mexico, how he uses poetic techniques in his prose and why India has come a long way for him. Edited quote:

What brought you to Mexico to write ‘Rosarita’?

Well, I first went to Mexico to escape the bitter North American winter. But when I got off the plane in a strange country, I felt completely at home. I thought I had returned to India; The resemblance between the two countries struck me immediately, and I kept coming back to Mexico. Rosarita to be a kind of patchwork, a collage of impressions from India that I have left and Mexico that is new to me, and trying to find how they fit together. My instincts told me that they were the right fit, but I couldn’t find the facts, the ground work needed for the foundation, until I found that I could put my confusion in the narrator’s voice. He is the one who creates the imaginary portrait of the mother who is no longer alive.

Why would you want to tell this dreamlike story in someone else’s voice?

For a long time I have wanted to experiment with using other people because it seems to me that it is a direct way to reach readers. The dreamlike quality, as you call it, is created by bringing in the trickster who is the figure of the magician. He plants the seed of this idea in the narrator’s mind that there is such a character, Rosarita, who studied art in Mexico, and although the narrator has never heard such a story from his mother and does not believe it, he cannot imagine that this is it. it might be true and what would happen to his mother if it is true. So, he created an imaginary mother.

Is the novella the preferred form these days? How does poetry shape your work?

I have tried to model prose in poetic technique for a long time, for as far as the little book I wrote, Fire on the Mountain (1977). I have tried to reduce the work to a set of images and use suggestions instead of any prosaic evidence. I always quote a few lines from Emily Dickinson’s poem to describe my work: ‘Tell the whole truth but tell it sideways / Success in the circuit of lies‘.

As for the novella form, I have come to it through a long circuitous route. In previous years, I wrote novels that were fully thought out and planned, but I preferred the novel form when I wrote the last book, The Vanished Artist, which is a collection of three novels. I am comfortable with this form; I can put everything I want in a short space, carefully selected and selected.

How to write before Salman Rushdie and deliver ‘Midnight’s Children’?

I will use my own experience as a model to answer your question. English for me is a literary language. It wasn’t the first language I spoke, but it was the first language I learned to read and write. So always belong to the book; the books and literature that I read are my models, and that shape my language into a more literary form of prose on paper. Although it existed before Rushdie’s work, like Raja Rao who tried to bring Indian intonation, like Mulk Raj Anand and GV Desani, Rushdie brought it to the present. He seems to speak English in India, on the street, in shops, in cinemas. He wrote about very serious subjects in this language, which encouraged the new generation to write about his Indian views, his experiences, using a foreign language but in the way Indians use it.

Has the India you know changed?

Unlike my parents who never returned to their homeland (Germany/East Bengal) because most of them were destroyed or lost, I was able to keep returning to India. But now I know that India has changed in the years that I have been away and I have changed in the years that I have been away from India, so it has become very distant. Now when I go back to India, I keep searching for the India I knew in my childhood and in my youth and I have to face the fact that this is no longer there.

Do you read contemporary Indian novels?

Many interesting things are done in the local language; translations have improved dramatically and books are more accessible. I usually book by Perumal Murugan; he writes about a small community in Tamil Nadu. The language is beautiful and well translated, so you can enter a world you have never opened before.

The cover of ‘Rosarita’ is a powerful, self-portrait of Amrita Sher-Gil.

This is a wonderful discovery made by my Indian publisher, Teesta Guha Sarkar. He was looking for Amrita Sher-Gil’s work with the idea of finding something suitable for the cover and he found this early self-portrait, which Amrita had painted when she was an art student in Paris in the 1930s. It was a very bold choice to make because I myself had not imagined or described the character of the mother or the narrator or the stranger, in fact, and the discovery of Teesta seemed very fitting. I have never seen this portrait, although I have been familiar with Sher-Gil’s work since I was young. I am dramatic for a young woman who has been painted, the gaze is determined and direct, and is wise. It gave me a great thrill to find myself on the same cover as Amrita Sher-Gil’s painting.

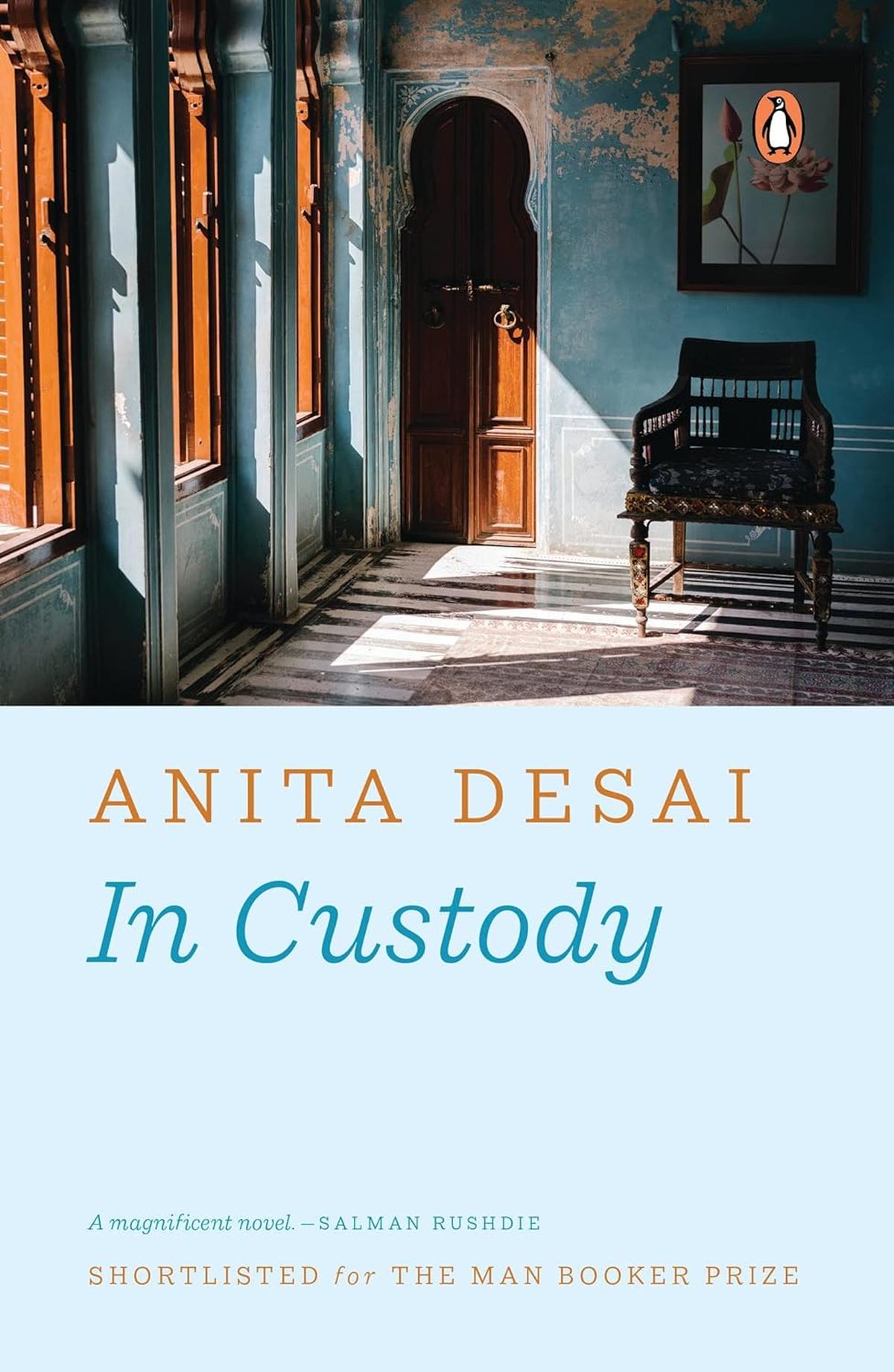

Some of your first novels revolve around domestic and interior circles. Does ‘In Custody’ react?

I have written many books about the world of Indian women which is mostly the domestic world. But there were times when I felt I had to step out of that domestic space if I wanted to write about a wider experience, not necessarily the world, but the Indian world. I thought that it would not be realistic to give an Indian woman an active public life. There have been women in the past who have lived extraordinary lives, but it is unrealistic to say that they are available to all Indian women. It has to be a male character who experiences the outside world – when I do, I find that the male experience of the world is mostly surrounded by other people. In Custodian also kind of experiment.

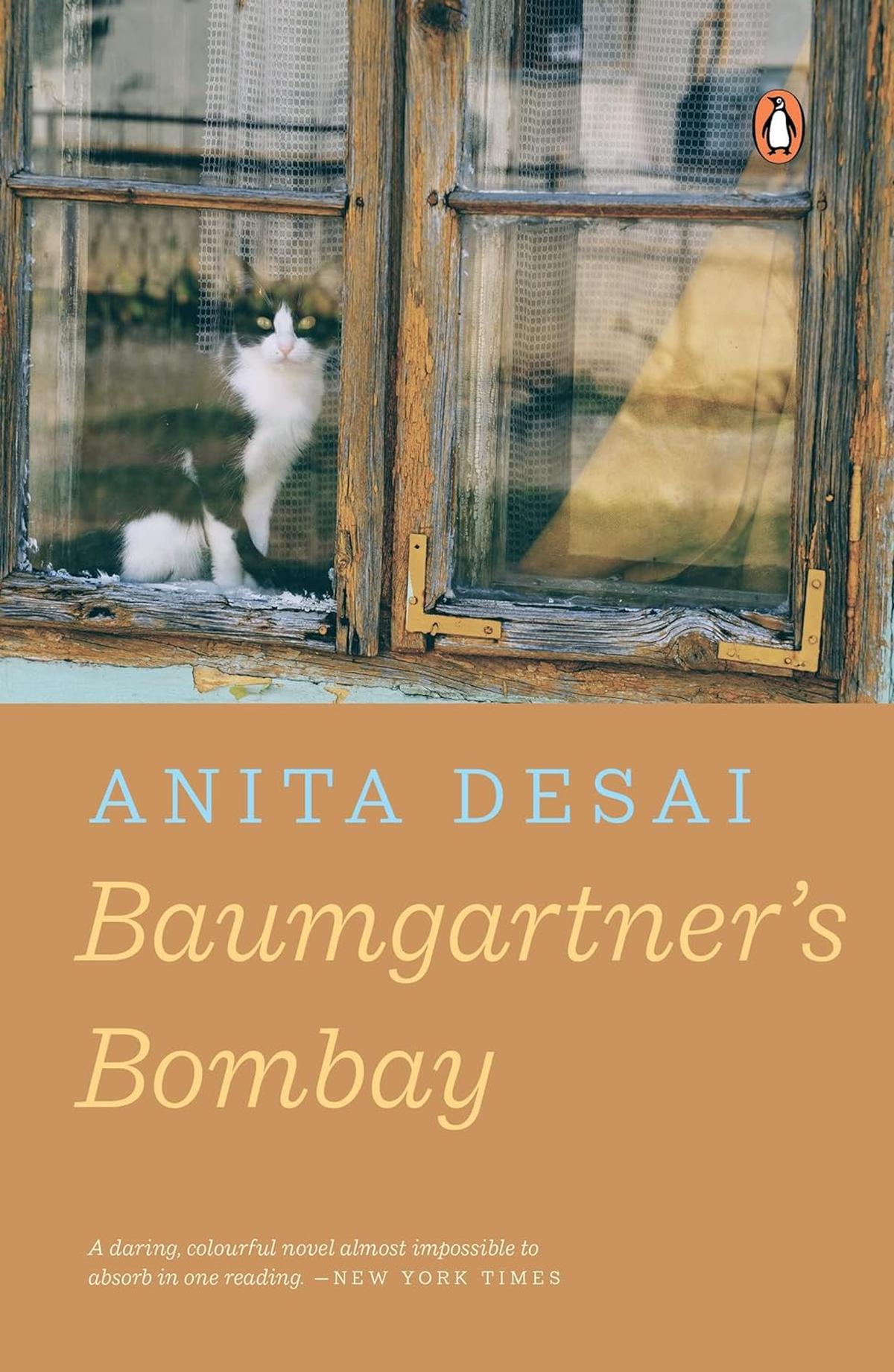

Which brings us to one of the extraordinary characters, Hugo Baumgartner, who lives with the fact that he is not “accepted” in his home country or in his exile. How did ‘Baumgartner’s Bombay’ come about?

Although I write in English and try to adapt to the Indian experience, there are other languages that I cannot express and I feel frustrated. For example, I have grown up with German because my mother is German. It must have been the first language I ever heard or spoke. It is the language of babies, the language of nursery rhymes but I have been silent all because how can I plant in the world of India? Then this name came to me – Baumgartner – which immediately marked the Germanness of this person and also his Jewishness, and having got that name, I then had to invent a life for him.

Any writers you’ve been reading and loving lately?

Jenny Erpenbeck’s work really caught my attention. He explores something new in every book he writes. The first book I read from him was Go, Go, Go (2015), which is about African refugees trying to settle in Berlin. I am also very saddened to hear about the unexpected incident of Ismail Kadare. I have read her novels, Twilight of the Eastern Gods (2014). He draws stories from his time as a young writer at Moscow’s Gorky Institute; writers from all over the erstwhile USSR were gathered there, and it was about the year that Boris Pasternak won the Nobel Prize that created such turmoil in the world of Russian literature. The book presented this world to us, and it was so fascinating that I decided to go out and find more of his work.

How do you write your day?

I always keep the morning free for writing, and even if I’m not working on a novel, I make some kind of writing, a letter or a diary, a note for a book I’m thinking of – spending time with pen and paper, and leaving the reading for later in the day.

What would you say to young writers? How do we deal with problems today, with the world changing? Is it easier to be outspoken these days?

It must be a good time for Indian writers; in fact, there are many things that have been heard, may have been taken into account, may have been thought about but not disputed or spoken. Now they have come to the fore, and it is inevitable, and it is time for young Indian writers to face the problem. We just take it for granted, that this is the way of the world. No one takes anything for granted, I think all young writers know that things can change. I know that this is hard to put into print, but I think that if we can insist on freedom of speech, then it can be done, so we should all speak freely, in writing, in speech. .

sudipta.datta@thehindu.co.in