According to Katy Prickett, BBC News, Cambridgeshire

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA series of French fashion engravings reveal how Samuel Pepys remained fascinated by the power of fashion throughout his long life, according to researchers.

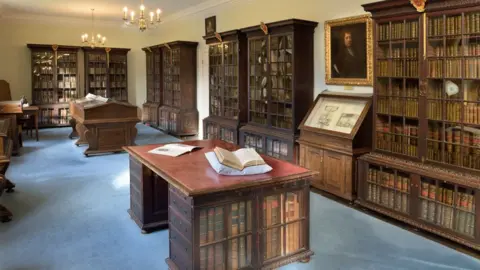

Best known for his diaries, the tailor’s son was also a bibliophile who gave a large library to the University of Magdalene College in Cambridge.

It includes one of the largest collections of late 17th century fashion prints in the world, eight of the which is published online for the first time.

Marlo Avidon’s research suggests that Pepys never shed his “anxiety” about dressing inappropriately for his station in life, despite his later success.

Marlo Avidon

Marlo Avidon“The need to be fashionable is very much aimed at women, but in many ways men are just as vulnerable, if not more so,” says Miss Avidon.

She studied the collection as part of her PhD research into the role of fashion in the construction of late 17th-century elite female identities.

“What is unique about Pepys is that we have documentary evidence in his diaries of his interest in fashion and also of his anxiety when people could quickly rise into the civil service and into the courts,” he said.

“You have to dress the part to assert your place in society.”

Magdalene College, University of Cambridge

Magdalene College, University of CambridgeThe diary of Samuel Pepys (1660 to 1669) shines a light on Restoration London, covering the ups and downs of his marriage, as well as events such as the coronation of Charles II and the Great Fire of London.

It includes an episode in which Pepys was “afraid to be seen” in a hot suit that he only bought “because it was very fine with gold lace in his hand”.

He finally worked up the courage to do so, only to be told by a socially superior friend that his sleeves were above his station. He decided he “wouldn’t appear in Court” with his sleeves and had the tailor cut them off.

At the end of his diary, the naval clerk (PNS) was at the pinnacle of professional success. In the following decade he helped establish the Royal Navy, became a member of parliament, was imprisoned in the Tower of London, was elected President of the Royal Society and died a prosperous man in 1703.

Magdalene College, University of Cambridge

Magdalene College, University of CambridgeA collection of fashion prints suggested episodes with sleeves do not put people off fashion – and French fashion at that.

The diary reveals his anxiety about the growing French influence on English culture, despite his marriage to Elizabeth, a Frenchwoman, and his friendship with a French merchant.

His wife died shortly after the couple left for Paris in 1669 and Miss Avidon believed that “this fashionable young lady’s print must have reminded Pepys of Elizabeth”.

The young housekeeper Mary Skinner quickly became his mistress and they remained together for the rest of their lives.

‘Culture and fashion’

Pepys’ active role in his wife’s education, including lessons in drawing and “raising women’s interests”, can be clearly seen in the diaries, Miss Avidon said.

He suggested that he did the same thing to Mary Skinner, which he did not know.

“I’m going to speculate, but you can see some pretty rough hand-colored fashion prints and it wouldn’t be a big leap to think these prints could have been a means of training Mary in drawing and fashion,” she said.

“When she died in the early 18th century, she was cultured and fashionable, leaving all her dresses to her nieces and imported Japanese screens and furniture.”

Magdalene College, University of Cambridge

Magdalene College, University of CambridgeThe PhD student admits what he knows about Pepys’s diaries has “clouded my opinion of him and Restoration society”.

Miss Avidon said: “A lot of it is rude and what I find is that he’s very jealous of his wife and very controlling and cruel to other women in his life, whether they’re close to him or random women on the street.

“He was also hypocritical about the debauchery of the Restoration courts when they acted more or less the same way.”

His research allowed him to see the correspondence later and now he sees “a very human person…Haunted by anxiety”.

“He is a man who can be brutal and cruel and also very funny and wise, and very on the nose about the world,” he said.

Miss Avidon’s research was published in the journal, The Seventeenth Century.

Douglas Atfield

Douglas Atfield