Richard Behar

Courtesy: Lizzie Cohen

You probably haven’t heard the name Bernie Madoff in a while, but that doesn’t mean the story of the infamous fraudster is over, or the pain he caused.

Irving Picard, the 83-year-old court-appointed trustee of the trust, still spends his days trying to collect money from the people who benefited from Madoff’s Ponzi scheme, and to reduce the staggering losses of others.

More than 100 legal battles over the most famous fraud in history are still raging.

Richard Behar, who just published a new biography, “Madoff: The Final Word,” is also still trying to understand how Madoff was thinking. What allowed people to rip off Elie Wiesel, who survived the Holocaust and went on to become a major historian? Or sit with his wife, Ruth, in the theater and enjoy a movie when he realizes that he has wiped out the savings of thousands of people around the world?

The question bothered Behar — who told CNBC that she has long been fascinated by artists. Long after most other reporters had turned their attention elsewhere, they reached Madoff while the financial criminal was serving a 150-year prison sentence in North Carolina.

Richard Behar’s book ‘Madoff: The Final Word.’

Behar began by sending his condolences to Madoff, whose son, Mark, had just died by suicide in December 2010, the second anniversary of his father’s arrest.

Soon, the subject line of an email appeared in Behar’s inbox: “Convict: MADOFF, BERNARD L.” The message was the start of a ten-year relationship between the two men, which included approximately 50 phone conversations, hundreds of emails and three personal visits. When Madoff died in April 2021, Behar was still writing the biography. Madoff often complained to Behar that he was on the book too long.

“He once joked that he was going to die on the way out, which was always true, even though I never planned it that way,” Behar said.

CNBC interviewed Behar, an award-winning journalist and investigative contributor to Forbes, via email this month. (The conversation has been edited and condensed for style and clarity.)

‘He never asks personal questions’

Annie Nova: You wrote that you’re an investigative reporter with a “special interest in scammers.” Do you think that?

Richard Behar: I’m always amazed at how scammers brain works. I’m particularly interested, maybe obsessed, with scammers who steal from people who are very close – like Madoff.

A scamster I visited in prison in the 1990s did something similar. Until Bernie’s arrest, this man ran the longest running Ponzi scheme, lasting 11 years. He was orphaned and raised by his aunt and uncle, but he was also fed up financially, as were his brothers, his wife’s parents, his best friend – even a nun who loved him for his faith in god. I was also not raised by my biological parents, and stayed in an orphanage. I can’t pretend to imagine that for those who stepped up to care for me, but endlessly pull for me. Maybe that’s where the fondness for scammers is rooted.

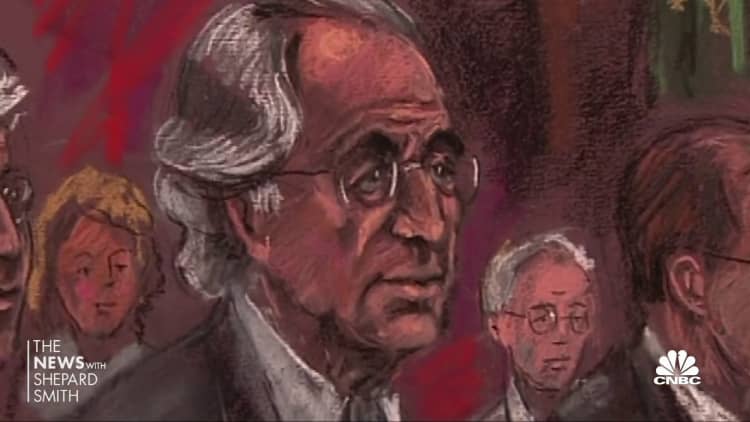

Bernard Madoff arrives in Manhattan Federal court on March 12, 2009 in New York City.

Stephen Chernin Getty Images News | Getty Images

AN: Did Madoff take an interest in your life?

RB: Through almost a decade-long relationship, he once asked me one personal question. That is mind-boggling. Sometimes I gave him an opening, like telling him that I grew up in a town not far from his hometown – with the same Jewish subculture but poorer – but he didn’t say anything. They don’t care. I asked a psychologist about this, and he thinks that Bernie is a malignant narcissist who can’t “hold reality, he can only hold himself.” I can’t be a three-dimensional human being to him, because if he can imagine, he must imagine a school teacher losing his pension.

AN: What’s the most exciting thing for you to see them show you what they’ve done?

RB: I once asked him if he could ever forgive himself for Ponzi himself, and he said, “No, never.” He insisted that he felt very sorry for the people he stole from. But I never fully felt it. Never shed a tear. I asked why he didn’t cry at his sentencing, and he snapped: “Of course I didn’t cry, I cried.”

‘Prison is a big relief for him’

AN: How did Madoff say life in prison changed him?

RB: He never talked about it. He once described himself as feeling numb. I said, “I can’t imagine what it’s like.” He replied, “You don’t want to know, you don’t want to know.”

In some ways, I think being in prison was a big relief for him. Running a Ponzi for half a century must be exhausting. In prison, he usually wakes up in his cell around 4 a.m., makes coffee in bed with an instant hot water machine, then reads, or listens to NPR until breakfast. He worked in the kitchen, then the laundry room and then supervised the inmates’ computer room.

The last job cracked me up because he said he could barely turn on the computer in his office, which should have been a red flag to everyone in the company that he wasn’t trading stocks.

AN: You wrote that he saw a therapist in prison. Do we know how often this is, or how long it lasts? Did it seem to help him?

RB: He ended the phone conversation abruptly because he had to attend a weekly appointment with a psychologist. When he called me, I asked how he was. She laughed and said that it was helpful, that she was a “very nice woman” and that she thought she should have done therapy years ago. But even though the sessions were helpful, she says she never found the answers she was looking for about why she was committing fraud and why she was hurting so many people.

NEW YORK – MARCH 12: Financier Bernard Madoff walks past the assembled press as he arrives at Manhattan Federal court on March 12, 2009 in New York City. Madoff is expected to plead guilty to all 11 felony charges brought by prosecutors in financial misdoings, and could end up with a sentence of 150 years in prison.

Chris Hondros Getty Images

He was troubled by press reports calling him a sociopath. She said she asked her therapist, “Am I a sociopath? Many of my clients are friends and family – how can I do this?” Bernie claims that he told them that people have the ability to separate, like mobsters who kill and then go home and arrest their children.

You just put it out of your mind. I asked if he came with a diagnosis. He said, no, just a compartment. Maybe he told her to make her feel better because she never came out.

AN: For years, it seemed like Madoff was just waiting to be caught. Is that true? Did he always know that he would never get away with it? What is life in a hanged country like for him?

RB: Bernie said he was in constant stress through Ponzi, and would talk out loud sometimes in the office, because of the pressure. One of his biggest outlets for stress relief is sitting in a dark theater with his wife Ruth, he says, watching movies twice a week. He also said he deluded himself into thinking a “miracle” would come to save him from Ponzi, but he knew at least a decade ago before his arrest that he would never make it out of the bottom.

The only time he was really relaxed, he said, was on the weekends when he was out on his yacht. I interviewed a former FBI behavioral analysis expert who suggested that Bernie felt safe on the boat because he could see 360 degrees around him, all the way to the horizon, so he would have a lot of forewarning that the threat would come.

‘Not a single investor’ complained to the SEC

AN: You paint a very interesting portrait of Irving Picard, the 83-year-old court-appointed trustee, who spent years trying to get money back for Madoff’s investors. Is this Picard’s only job over the years? Why did he make this his life’s mission?

RB: Picard rarely speaks to the press. I just talked to John Moscow, a former white-collar crime prosecutor for the Manhattan DA’s office who worked on several Madoff cases for the trustee. He said: “Irving was a very dedicated public servant.” He is laser focused on the task at hand. John’s words: “He’s not manic about it, but he’s very close.”

In my book, I quote a former federal prosecutor who said you could investigate this case for 50 years and still not know the whole truth, but Picard wasn’t interested. This is the only bankruptcy case since four days after Bernie was arrested in 2008. He hates net winners who won’t return funds, but he can be a soft teddy bear with people who don’t have money for him to return. . He can let them pay over time, or he will take someone’s house but leave a life interest in it.

AN: What do you think people are most wrong about Madoff?

RB: Many people lose money wrongly because they blame themselves, instead of looking in the mirror and asking themselves how they could have met the danger. Madoff’s consistent and high returns are simply untenable. Even so, many losers think the government owes them money because the SEC didn’t catch Bernie. But the agency’s mandate has never protected people from foolish investment decisions.

Financier Bernard Madoff arrives in Manhattan Federal court on March 12, 2009 in New York City. Madoff is scheduled to enter a guilty plea on 11 felony counts that under federal law could result in a sentence of up to 150 years. (Photo by Stephen Chernin/Getty Images)

Stephen Chernin Getty Images

I told you that I went to prison in the 90s to visit the longest running Ponzi before Madoff was arrested. Like Bernie, these scammers couldn’t have done it without the involvement of the big banks. In that case – an 11-year-old Ponzi – investors reached out to the SEC to complain that they lost money even though they had been guaranteed a return of 20-25%. The fraudster was arrested the next day.

In Bernie’s case, not a single investor during half a century of fraud contacted the SEC. They were too busy splashing around in the gravy.