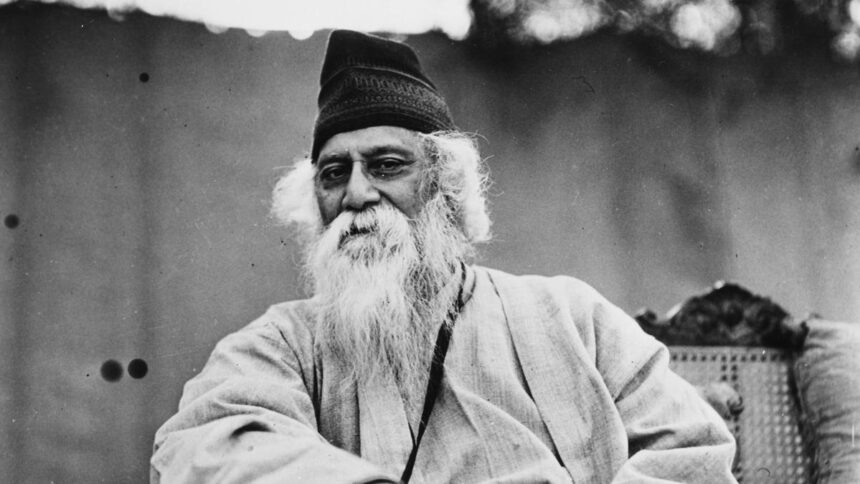

Rabindranath Tagore Photo credit: Getty Images

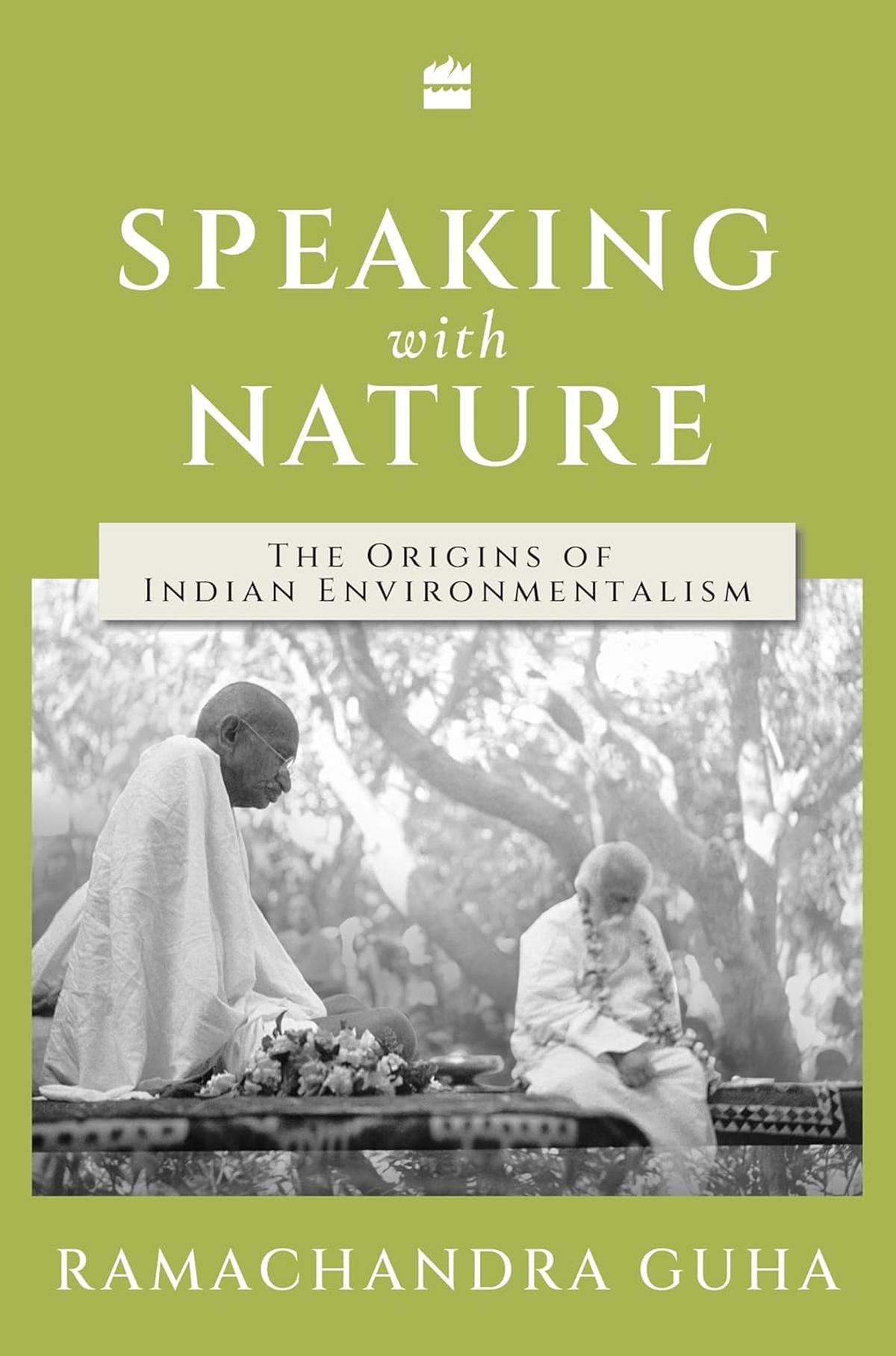

Environment is not just an idea; it is also a verb. In his latest book, Talk to NatureHistorian Ramachandra Guha draws a portrait of ten people who are credited with laying the foundation of environmentalism in India.

One would expect a list of tribal leaders, hunter-turned-conservationists, (‘repentant butchers’ as the author says in one part of the book), who have spearheaded environmental movements, or professional conservationists and administrators. Guha though presents us with an unexpected selection of people – writer Rabindranath Tagore, sociologist Radhakamal Mukherjee, Hindutva thinker KM Munshi, naturalist M. Krishnan, Gandhi follower Mira Behn, anthropologist Verrier Elwin and others.

Link with social thinking

Guha continues the question that has been asked in previous writings, as he describes the ‘full belly environment’ – the Western idea that environmental awareness can only come out of prosperity (which shows that Indian thought cannot be environmental). The people selected in this book, eight men and two women from around the world, connect nature with broader social and political thought with reference to India. Another thing they have in common is that they write about ideas, and are scholars. Refreshing, this book leans on various sources to piece together the ideas Guha put forward. Readers may recall Jairam Ramesh’s book on Indira Gandhi as an environmentalist (Live in Nature); This book also uses letters, speeches and papers as sources.

Mira Behn Photo credit: Getty Images

I read with great interest about Mira Behn, the only woman in this book (the other lady is one half of the married couple who advocate for ecological agriculture, Albert and Gabrielle Howard). Mira’s writing is interesting for two reasons. One is its relevance to the present day – one of his concerns is the disturbance of fir trees in the Himalayan oak forests, a problem that still exists (and is getting worse due to human-caused disturbance and fires); another is the disappearance of the Haldu tree, which still does not get the ecological importance it deserves. The rest is his question to the forest department unthink. In many passages, the book not only assesses the problems of India a century ago, but is a reflection of the problems we face today.

Guha writes about Tagore describing the city as a parasite, the anthropologist Elwin describes the Gond understanding of nature as beautiful and savage, which is increasingly true in climate change.

M. Krishnan | Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

In Tagore and Mukherjee, Guha recalls his fondness for trees with “rolls”, the banyan tree. Guha wrote that Krishnan disliked Indian animals given Western nicknames (for example, Gaur was mistakenly known as bison). Playfully though, Guha calls Krishnan India John Muir. Krishnan is a naturalist who writes about all animals, whether big, small, endangered or common; and like Muir he also advocated for an untrameled view of nature, Guha argued.

Skillful framing

In framing a good environment not as an abstract or aesthetic concept, but as something related to the economy, agriculture and other areas of general interest, the book may seem like a prophecy of the future. We still need a more ecological path to development, not crumbs from the table of industrial growth.

Guha’s skills are in-depth questioning and looking at various sources to create a detailed account that can be called interdisciplinary; this book is likely to surprise you. As a conservation biologist, I would be interested to read Guha’s writings on current environmental fermentation of non-humans. Such as the growing Natural Rights movement; and in the tree that shows so much – the political and environmental history of the banyan.

Talk to Nature; Ramachandra Guha, Fourth Estate, ₹799.

The reviewer is a conservation biologist and the author Wild and Wilful: Tales of 15 Iconic Indian Species. He tweets at nehaa_sinha

Published – 15 November 2024 09:02 IST