When Rafael Nadal retires from professional tennis next month, the sport will be missing something.

It will lose a powerful athlete whose burst on the court will surely send tennis ball-shaped torpedoes flying over the net – not damaging the racket. No one going forward will be an obsessive player whose mid-game ritual appears to the casual fans, as they do in every match. Tennis will say goodbye to a humble man who remains unwavering, even when he won two Olympic gold medals and a staggering 22 Grand Slam singles titles, extraordinary – and possibly unrepeatable – 14 of them on the red clay of Paris.

And will say goodbye to the tennis player whose childlike love for the game never dampened, even when he changed his own sport.

After more than twenty years in the pro circuit, countless injuries – and like many comebacks – Nadal announced on Friday that the final tournament will be the Davis Cup this year, where next month he will play for his home country of Spain.

Over the last two decades, 60 Minutes reporter Jon Wertheim has seen it all; he has covered Nadal for Sports Illustrated and the Tennis Channel since the tennis phenom was 18.

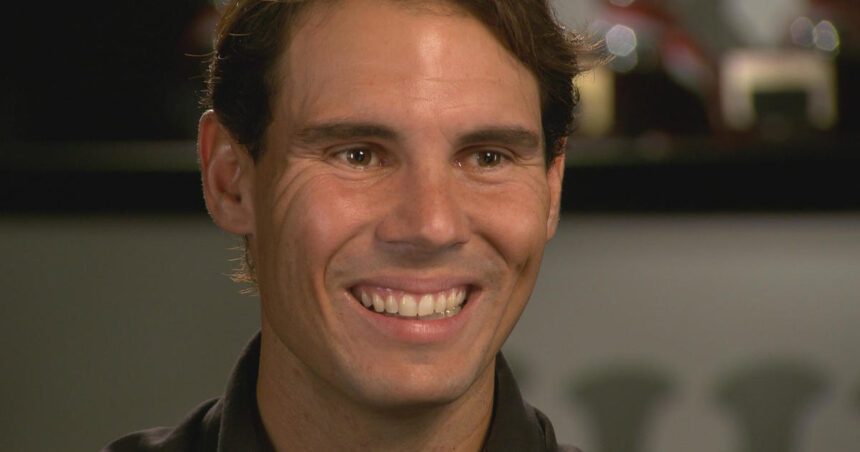

In 2019 for 60 Minutes, Wertheim meets Nadal in his hometown of Mallorca, the Spanish island where he was born and still lives. The two shared a long sit-down conversation unusual on the tennis circuit: It was in Nadal’s hometown, not at a tournament, not when he had a match the next day, not when he was thinking about slicing a backhand.

In that conversation, it became clear how much love Nadal has for the sport.

“I never felt that what I did was a sacrifice,” Nadal told Wertheim through a Spanish interpreter. “I’m training yes, I’ve been working hard, to the max, yes. But I like everything. For me, sacrifice means you do something you don’t like. But I’ve done it. all the things I want.”

60 Minutes opened in December, the number of weeks for the off-season in tennis. But instead of using the time to rest before the start of the new season, Nadal is working hard, honing his southpaw forehand and double backhand.

Wertheim watched as Nadal played his morning practice with characteristic vigor, sending the ball swinging the racket with the speed usually reserved for matches. His concern served him well on the court. It also takes a toll on the body.

“I’m very happy that after all the physical problems that I had to suffer during my career, which was a lot, I’m happy that I’m here at 33 years old,” he told Wertheim in 2019. “It’s something I want and it gives me great personal satisfaction.”

Over the years, Nadal has suffered from physical injuries, occasionally taking time off to rehab. Each time, they seem to progress and get back to the top of their game.

In a way, struggling through adversity is what Nadal told Wertheim he likes most about tennis itself.

In a 2019 interview, Nadal said that he likes the “mental effort” of the game, looking for solutions while in the set, the analysis needed to change the dynamics of the match. When he loses, he wants to know what went wrong, to analyze how his opponent played better that day.

If he came from behind to win, he said he found victory even more satisfying than, say, trouncing a competitor in straight sets.

“Because you put in the extra effort,” he said. “It means you have a chance to compete again the next day. And the next day, you’ll play better. Sometimes when I’m in the first round or the second round, and I’m not playing well. I say, okay, just accept it, don’t get frustrated .

Focus has become a key element of Nadal’s game. To block distractions – from the crowd, from the opponent, from his own head – he created a ritual that he performed every match. He told Wertheim that about an hour before the game started, he talked to his coach. Then, he thought to himself as he readied his grip on the racquet and the physiotherapy bandages. Before walking out onto the field, he walked into the ice shower.

On court, routine also precedes each serve. Nadal stepped forward and leaned his weight onto his right leg as he adjusted his shorts behind him. Then, when methodically dribbling the ball with the racket in the left hand, the right hand takes the sleeve on the left shoulder, then the right. He gave a quick swipe to his nose before tucking the hair behind his left ear, then repeated on the right side – nose swipe, hair. With a final wipe on each cheek with a sweatband, he was ready to serve.

Then, when he returned to the seat on the side, there was a bottle of water. He always placed two bottles in front of his chair, one behind the other so that they faced the court diagonally. He turned the label out. Before the match and during the changeover, he took alternate sips from each before placing them on the board with precision.

It may seem like superstition, but Nadal explains that it’s all part of his way of ignoring distractions.

“If I don’t do it with the bottle, then I sit down, I might think about something else,” he told 60 Minutes in 2019. “If I do the same thing, it means I’m focused and I’m alert to think purely about tennis.”

Wertheim witnessed many of Nadal’s rituals during the two decades he covered the tennis star. When Wertheim first profiled Nadal for Sports Illustrated in May 2005, the young Spaniard had yet to win a major title. But Wertheim saw potential in Nadal’s passionate playing, writing, “(T)here is every indication that Nadal … has begun a long place at the top of the sport.”

And yes. Nadal entered the Top 10 of the Association of Tennis Professionals that same year and spent 912 consecutive weeks in the Top 10. He only stopped in March 2023 after injuries sidelined him for the rest of the season.

One of Nadal’s most lasting legacies is his rivalry with Roger Federer. They met over the net 40 times, faced off in European clay, hard courts of the distant sea, and the grass of London. There, the pair played one of the best matches ever played: the 2008 Wimbledon final, a battle that lasted nearly five hours on court, not including two rain delays. In the end, Nadal beat Federer, who had won the title at Wimbledon five years earlier, ending Federer’s 40-match winning streak at the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club.

But the duo is perhaps best remembered for their true friendship.

“We … know that this is a game,” Nadal said in 2019. “And there are many other things in life that are more important than the game, than the match. And of course, there are some more tense moments. But like everything else in life , both (Roger) and I, we have been very clear in our minds that human relations are more important than tennis rivalry.

When Wertheim spoke with Nadal for 60 Minutes five years ago, Federer had 20 majors. Nadal has 19. When he retired Next month, he will walk off the court with 22 – two more than his old friend, and two less than the remaining members of the “Big Three,” Novak Djokovic. Of the three, perhaps Nadal’s place in history is the most important.

And in 2019, he told 60 Minutes that he will be at peace, whenever he returns to his final service.

“I’m not worried about retiring at the end of my career,” he said. “I just want to have fun and enjoy playing as much as possible. And when I retire, I think there are a lot of things in my life that will make me happy.”

The video above was produced by Brit McCandless Farmer. It was edited by Scott Rosann and Sarah Shafer Prediger.