After almost two and a half years of fighting, it is unclear how many Ukrainian soldiers have been killed or wounded. However, the limited data released suggests that there are tens of thousands.

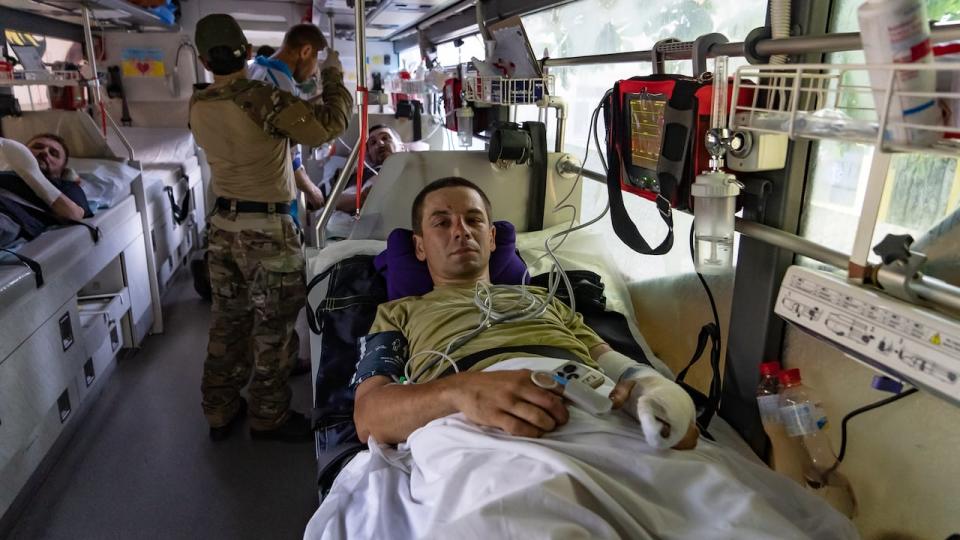

CBC News recently gained access to a medical evacuation bus transporting wounded soldiers from the front lines to a hospital in Dnipro Oblast in Eastern Ukraine.

The 25 patients who were evacuated in the bus that were released voluntarily included those who had been conscripted under the new mobilization law and sent to the front with only basic training, along with those who had volunteered to fight at the beginning of the war.

Here is what some of them told us.

Hit by a grenade launcher

Most active Ukrainian soldiers will allow themselves to be identified only by their call sign. The 39-year-old IT specialist is known as “WIFI,” and his time on the front lines has been brief. He was wounded after two and a half days at the front. They have been deployed to a position near Pokrovsk in the Donetsk region, an area Ukrainian officials have described as experiencing some of the most challenging combat ahead.

WIFI told CBC News that he was in the trenches just hours earlier, helping to reinforce, when he was attacked. He said there was fire from Russian automatic grenade launchers.

After the first shot, he said, fragments flew into his thigh. “It felt like a needle injection,” he said.

The second shot hit him in the opposite leg.

“It was red-hot and immediately, there was a sharp pain and numbness in the leg.”

He used a tourniquet on the limb to stop the bleeding. But after getting stuck, he couldn’t crawl out of the trench, so he had to be carried by two of his friends.

When CBC News spoke to him, he was sleeping on a stretcher outside an unidentified pickup point, texting his mother.

He said he was exempt from conscription because he had cancer, which was in remission, but when Ukraine passed on new mobilization lawit removed some medical exemptions, and he became eligible.

He said military officers came to his home in Poltava in late April. After receiving training for about two months, he was sent to the front and was able to return after his recovery.

It will be up to the medical commissioner to decide whether he can be recalled.

“It’s really tough mentally and physically,” he said of the time ahead.

Pinned under the tank

Before this 34-year-old soldier, who goes by the call sign “Liahk,” was mobilized in April and sent to the front last month, he worked as an accountant in the western Ukrainian city of Lviv.

He was in a tank on the front lines in the Donetsk region when at approximately 7 am local time on June 19, he was hit by a Lancet drone. The drone, which self-destructs when it hits a target, was first used by Russia in Syria and has been used repeatedly in Ukraine to target weapons and artillery on the ground.

After the tank was hit, part of the turret collapsed, pinning Liahk and his commander inside. The tank driver got out and started pulling Liahk out, but then shouted that they should try to start the tank again, because they would probably come under fire twice.

“It was a miracle the tanks started, so they drove us out,” Liahk told CBC News as he grimaced and waited to board an evacuation bus.

As they exited the combat zone, the commander continued to speak to Liahk before he lost consciousness and lapsed into a coma.

A narrow escape

A soldier with the call sign “Kniaz,” which means prince in Ukrainian, stood out among a group of soldiers CBC met, as he turned 60. On June 19, Kniaz drove a military vehicle to Avdiivka, ie captured by Russian forces in February, when the vehicle was hit by a projectile dropped by the first-person view (FPV) drone.

Shrapnel pierced the head, shoulders, arms and legs. He said he was able to escape the vehicle quickly saving his life as the vehicle caught fire.

“Drones bother us the worst,” he told CBC News. “We don’t have as many as those Russian bastards.”

Unlike some of the other evacuees, he volunteered to fight at the start of the Russian invasion on February 24, 2022. He also previously fought against Russian-backed separatists in Donetsk in 2017.

“It is everyone’s duty to defend the motherland,” he said.

Eliminates fear and tendency to injury

Tatiana Romaniuk, 33, isn’t a soldier, but she has a call sign: “Rudy,” which means redhead, a nod to her long copper hair. He is a combat medic Hospitala group of volunteer paramedics, and spend two weeks a month transporting wounded soldiers to hospital.

The repurposed bus carrying soldiers has six beds inside along with medical equipment. On the day CBC opened, it was sweltering inside, and the heavy smell of sweat and blood hung in the air. Romaniuk was about 40 degrees C inside the bus.

The most seriously injured are taken on stretchers to their beds and immediately connected to medical equipment that measures heart rate and oxygen levels. Others were crammed into the ship in any available space. Some were lucky enough to get seats while others sat in the aisles.

Medical evacuation may occur with prior notice. When soldiers are wounded at the front, they receive immediate medical treatment at the military stabilization point and are then transported to the pick-up point, where they are met by Hospitallers and transported to the hospital.

Romaniuk said the most difficult part of medical transport is when a soldier breaks down on the road, as happened to the patient when CBC was on the bus. After arriving at the hospital, the soldier required emergency surgery for shrapnel lodged in his spine.

Romaniuk said the first thing the trained soldier did after just one week at the front when he got on the bus was to borrow his cell phone and call his family.

He said a common question all soldiers are asked when they are being transported is whether a limb should be amputated.

“They’re worried about how they’re doing, what they’re going to do next and what their life is going to be like,” he said.