Book Review

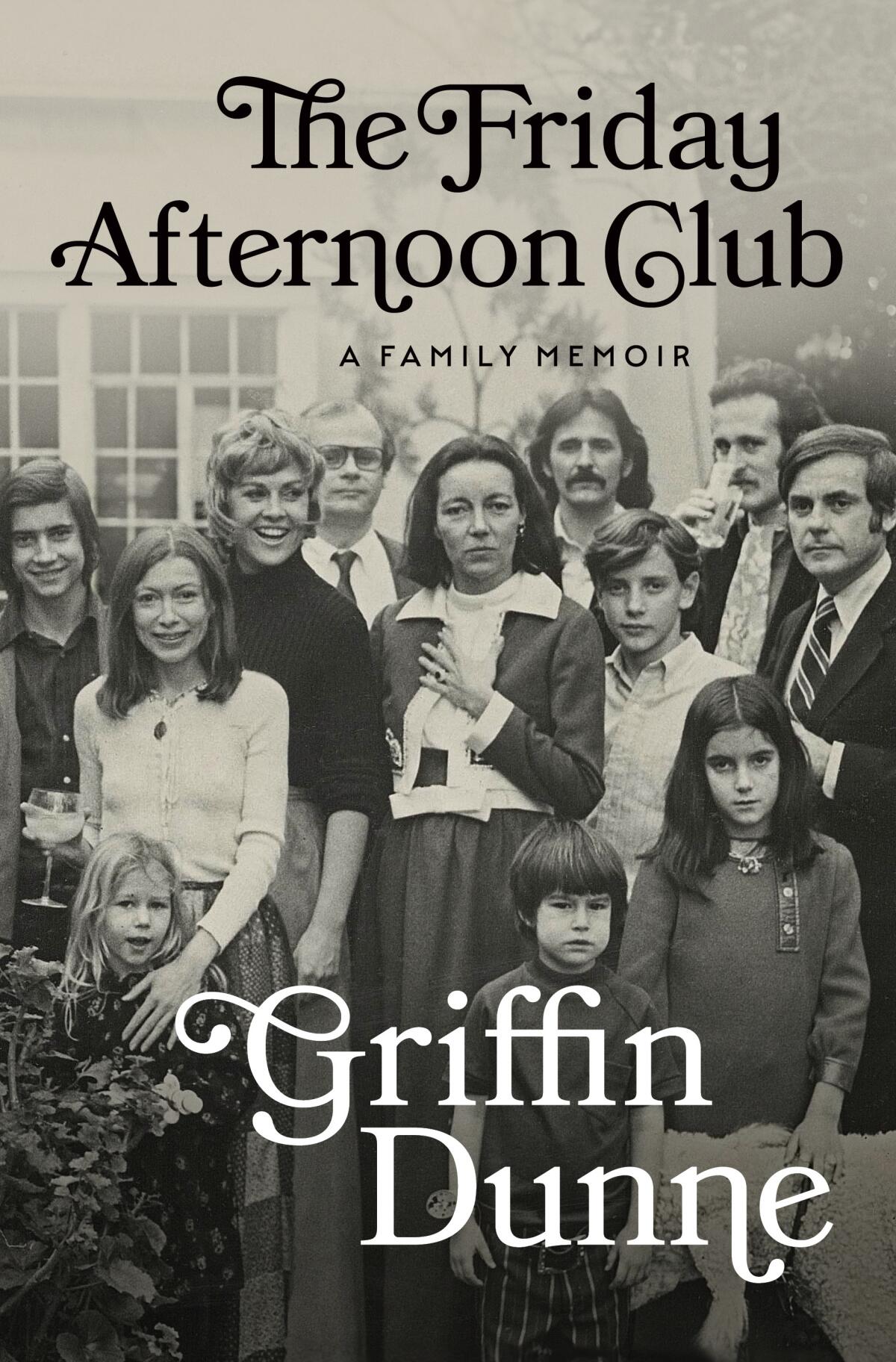

The Friday Afternoon Club: A Family Memoir

By Griffin Dunne

Penguin Press: 400 pages, $30

If you buy a book linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, which costs support independent bookstores.

Life is what you make of it, especially when times are tough.

For example: It’s midnight and you’ve arrived in SoHo to see a woman you met at a restaurant but she’s not all she seems and you can’t pay for the subway home because money is flying out of the taxi window on your ride downtown. you bum around but you end up getting mistaken for a thief and then a woman from a diner overdoses and before you know it you’re being chased by a crowd of punks led by a vigilante driving a Mister Softee truck. But you can still work on time.

Of course, this is the story of Martin Scorsese’s dark screwball classic “After Hours,” but, based on his own testimony, it could be a night in the life of the film’s main actor, Griffin Dunne. In his new memoir, “The Friday Afternoon Club,” Dunne, who will be nominated for a Golden Globe for his performance, remembers the first time he read the script.

“By page ten, the terrible things that happened to the hero of the story made me so anxious that I couldn’t read sitting down,” he wrote. “I am perfect for the role. The misadventures of Paul Hackett, the main character, could only happen to me.

Another title for “The Friday Afternoon Club” might be “The Misadventures of Griffin Dunne.” In the book, which focuses mainly on the first 35 years of his life, he was “beaten and arrested” (boarding school), humiliated (often), almost killed in street fights, fired, arrested, labeled “second. -rate Dudley Moore” by Pauline Kael and molested by Handy Tennessee Williams.

Dunne generally carries these slings and arrows with good humor and balance, self-conscious, perhaps, while retelling himself as a joke hero. He got good mileage out of his own luck.

There is luck as well. Dunne grew up privileged in freewheeling Hollywood in the 1960s and 70s, the eldest of three children.

His parents, Lenny and Dominick Dunne, and his aunt and uncle, writers Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne, enjoyed a very good social life. Guests at one party included Truman Capote, Natalie Wood and Tuesday Weld. Sean Connery saves him from drowning. Elizabeth Montgomery, later Samantha in “Bewitched,” baby sat her.

Then, her best friend and roommate in New York is Carrie Fisher (Debbie Reynolds pays the rent). In one chapter, Fisher contrives to lose her virginity to our hero, who turns out to be something of a Don Juan type. “Down for the girls is what I do for life, pro bono,” he wrote.

But for all, “The Friday Afternoon Club” is haunted at the core by a terrible family tragedy.

The worst night of Dunnes life plays out twice in the book. In a brief prologue, we read about the night in late 1982 when homicide detectives knocked on the door of Lenny Dunne’s LA home with news that his daughter, Dominique, had been strangled and was in intensive care. Griffin, then 27, could still taste the cocaine from the night before in his throat when his father called him.

The night jammed through hundreds of pages of family history and childhood memories before Dunne returned to the story. The death of Dominique, a rising star through his role in the year’s hit movie “Poltergeist,” and the trial of his ex-boyfriend John Sweeney is the subject of the last act of destroying the book.

What makes this event unimaginable so that it can be read, and allows Dunne to find a kind of grace despite the tragedy, is unshakable black humor and an unfailing nose for a good story.

Perhaps the ability to mine the worst experience for a good copy is inherited. After all, Dominick Dunne’s last success as a journalist began with a blockbuster account, in Vanity Fair, from Sweeney’s trial. Griffin was initially ambivalent about the piece, doubting his father’s motives and feeling that the family’s grief was not for public viewing, but he later admitted that it would become “a Bible that I would share with anyone I thought could be a part of my life.”

Indeed, it is possible that Griffin’s account of this terrible day was shaped in part by Dominick; many details recall the Vanity Fair essay, and father and son seem to share a cautious appreciation of the black comedy of fate. Both found dark humor, for example, in the disaster of Dominique’s funeral, bungled by the pickled monsignor who was double booked with the wedding.

Dominick wrote: “When the driver opened the door for us to get out,” Dominick wrote, “the hot wind blew colorful party confetti into the car.” Griffin continued: “As Dominique was lowered to the ground, the tour bus dropped off spectators in front of Marilyn Monroe’s columbarium.”

One can also detect the influence of aunt Joan, especially in Dunne’s levelheadedness and strong eye for material, but painful.

In “The Center Won’t Hold,” a pricey Netflix documentary made about Didion in 2017, she asked what it was like to watch a 5-year-old girl take LSD, an incident she wrote about in “Slouching Towards Bethlehem.” After a pause, Didion said, “Let me tell you, it’s gold.” Dunne, too, is a prospector for incandescent details.

In the end, Dunne shows the power of writing and the temperament to turn the central tragedy of his life into something more than just a story of suffering.

Like the character in “After Hours,” there are always times when he might throw up his hands and scream “What do you want from me?” However, he finds solace in Dominique’s memory for as long as he has been gone.

He is a guardian angel; he felt he was on the last page of a peaceful book, as he enjoyed holding his first daughter. Even the title of her memoir is Dominique – The Friday Afternoon Club is a weekly but memorable meeting with her acting friends.

This is a detail that, in retrospect, gives life a richness that makes it worth enduring and celebrating, despite everything.

Charles Arrowsmith is based in New York and writes about books, movies and music.