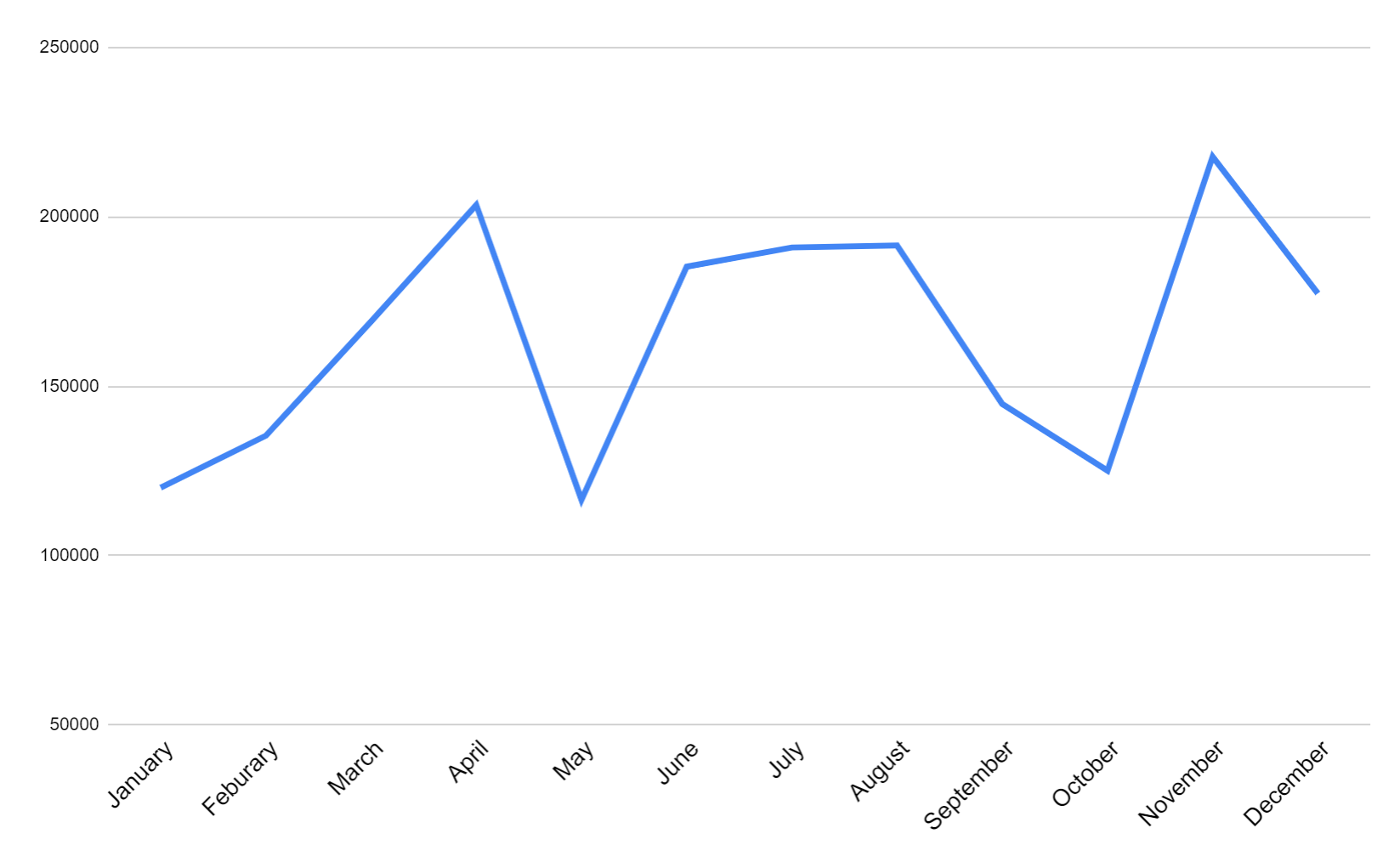

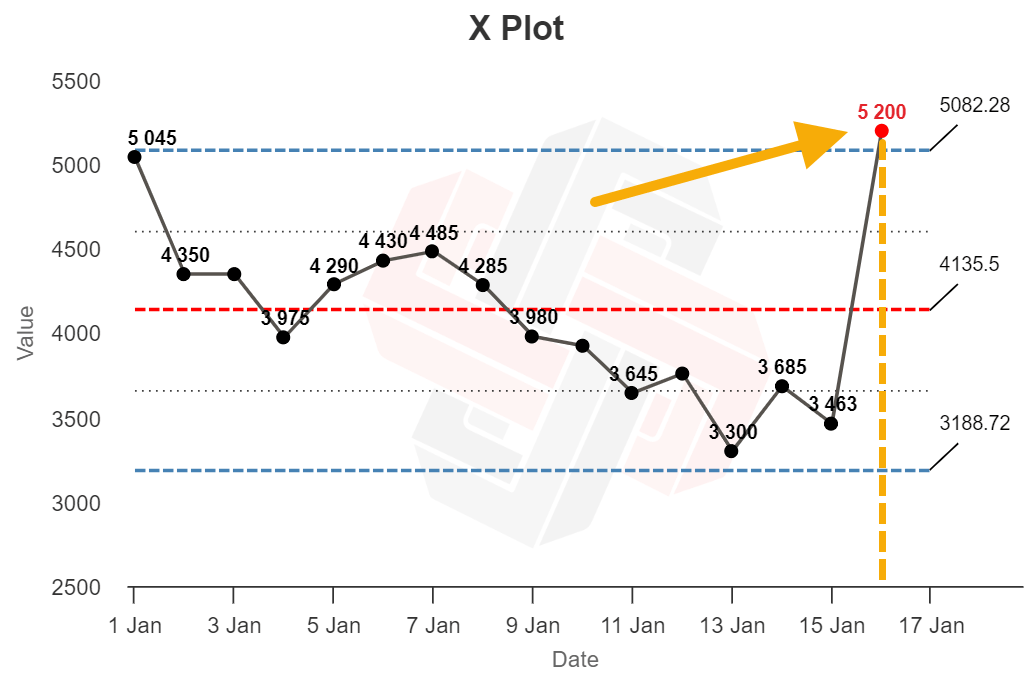

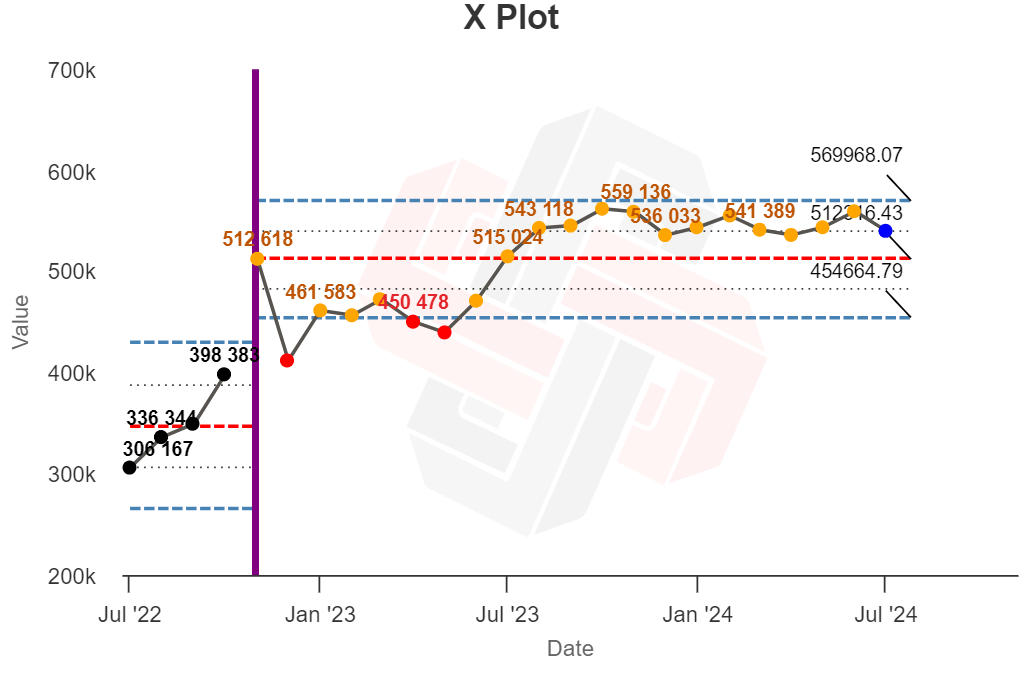

Website traffic data usually looks like this:

Ups and downs, peaks and troughs.

If we’re doing our job right, most of us expect traffic to pick up over time, but in any given month, it’s hard to tell whether peaks or troughs should be taken into account.

Are we doing something good and triggering a new phase of growth? Do we benefit from the new Google update? Or is it just a normal variation, part of the natural ebb and flow of people finding our website?

Or suppose you made a change in your content process—you pruned and redirected a bunch of old content—and then your traffic dropped the next month. What a drop caused by change, or is this just a coincidence?

I have tried a simple statistical tool designed to answer this question: XmR graphicsalso known as process control charts.

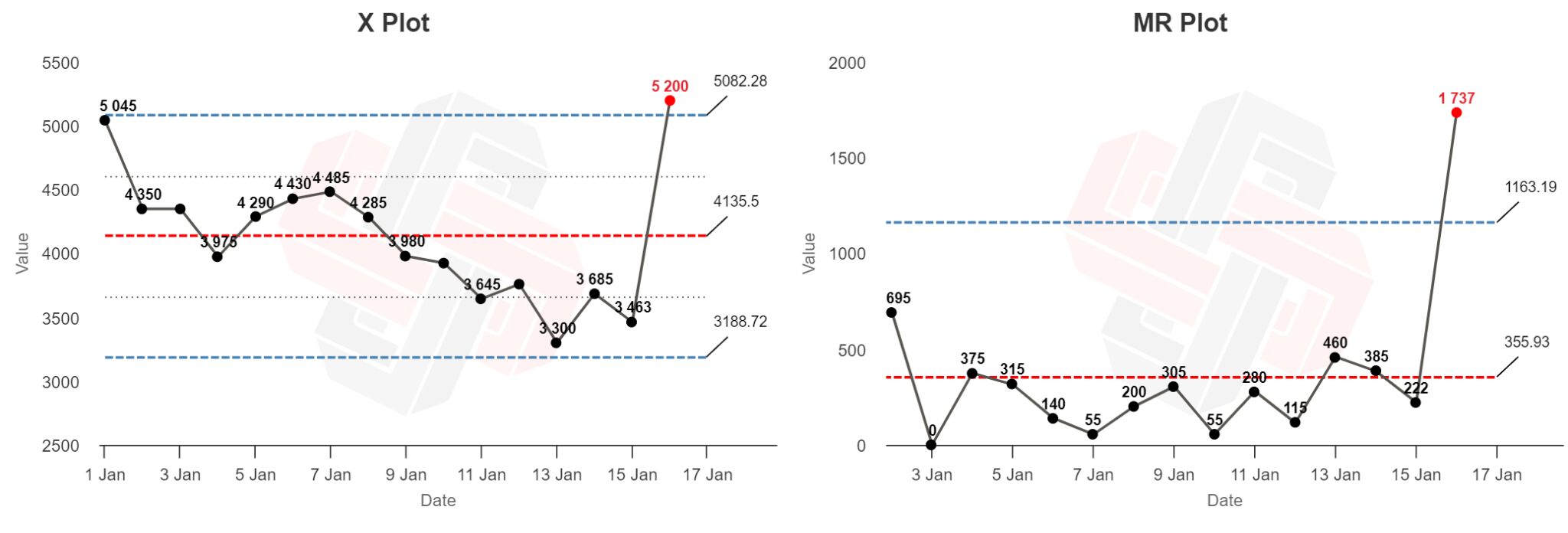

Here is the XmR chart:

XmR charts are designed to tell you when a single data point in a time series may be due to normal fluctuations (“routine variation”) or a sign that something is happening and should be investigated (“extraordinary variation”).

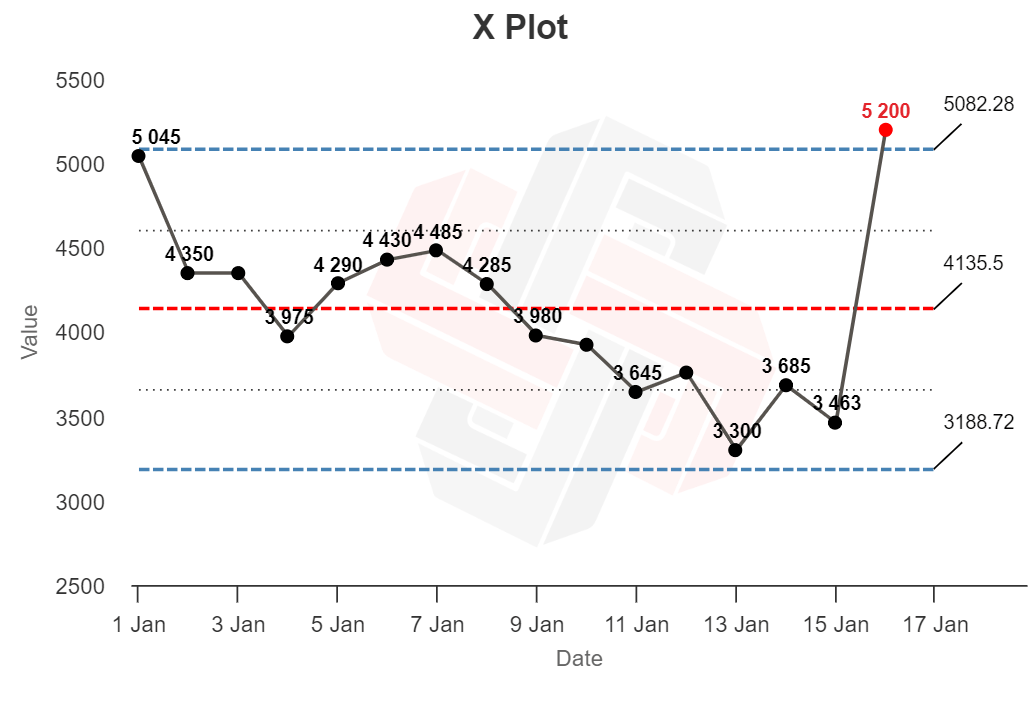

XmR charts include X plots (named after the value of x“things” we care about – like widgets produced or sales closed)…

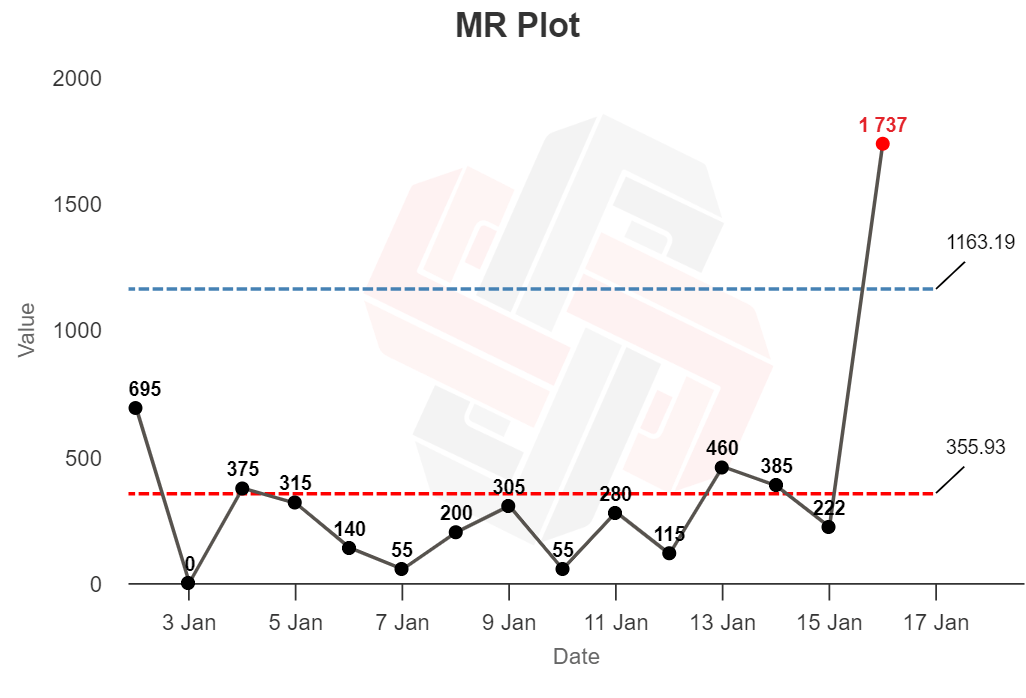

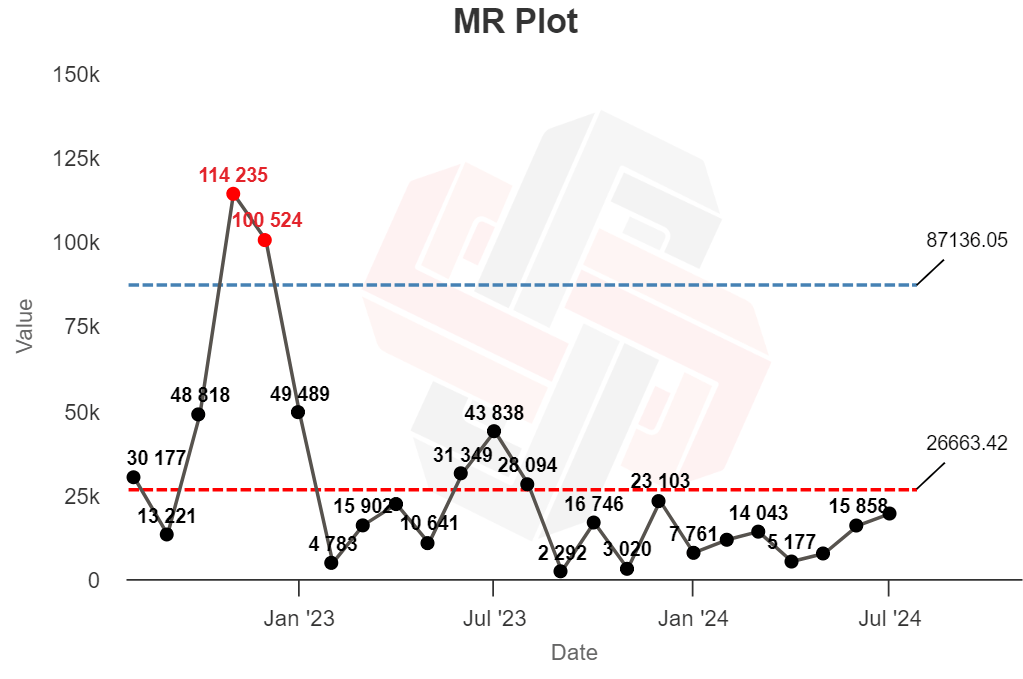

…and the MR plot (named after some movingBasically the “gap” between each data point):

In its simplest use, if you plot the data on a chart and shake it up and down around the center line, without crossing the upper and lower limits—no problem! These ups and downs may represent normal variations.

But any point that appears outside the upper or lower bounds (see in red) should be considered an anomaly to be investigated.

In the X plot above, the time series appears to show regular variation until January 16, when the first red-bound exit point appears.

The XmR chart shows that something happened on the 16th to mess with our production process (for better or worse). Our job is to investigate why.

Side note.

The row in the middle is the average value of the dataset; The upper and lower bounds indicate 3-standard deviations away from the mean (known as three sigma). Any point outside these upper and lower bounds may be anomalous, and not part of the original probability distribution.

There are other “signals” that the XmR chart can show you (like eight consecutive points on either side of the average line representing another type of exceptional variation) – but I will leave you to investigate that in your own time.

When I started reading about XmR charts, there was one obvious use: identifying the impact of Google algorithm updates.

If the site’s traffic goes to zero, it’s easy to say “we got a manual penalty.” But for smaller changes, like a steady decline in traffic over several months, it’s harder to pinpoint the cause. Are we caught up with the Google update? Is it seasonal? Or is it just a coincidence, with traffic returning to normal in the future?

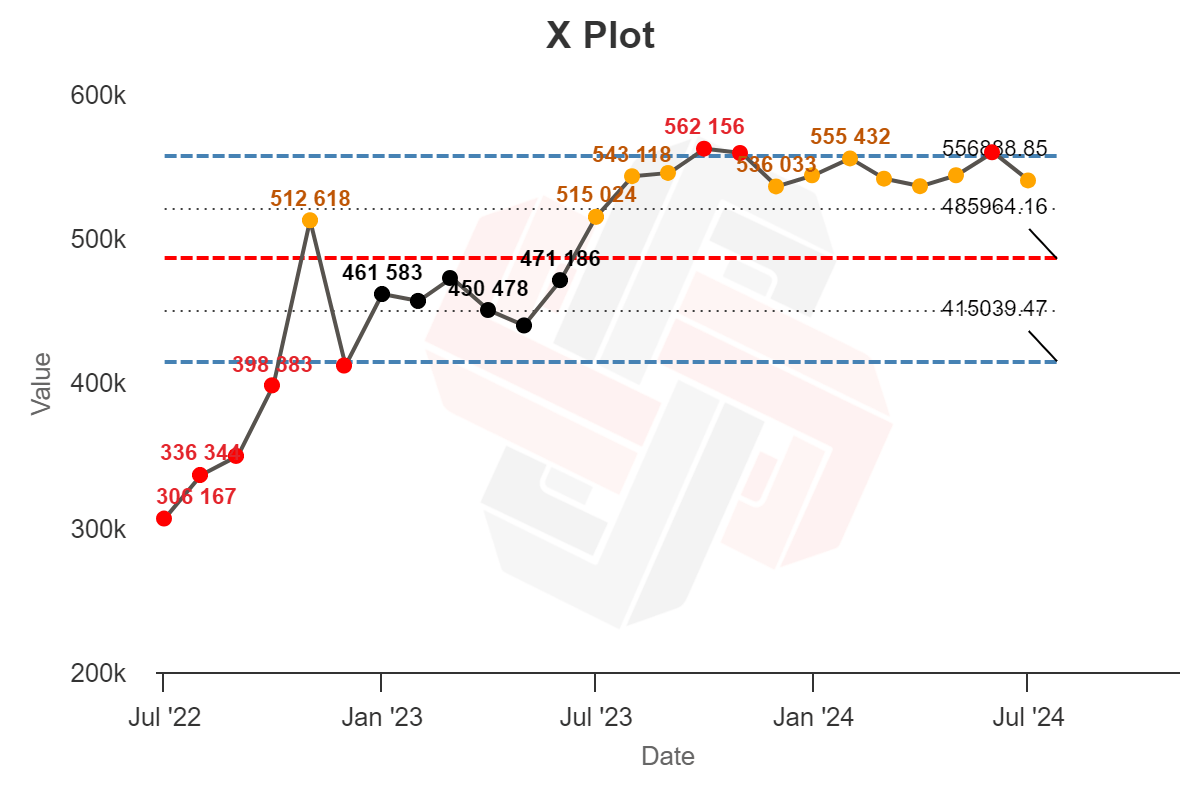

Here are two years of monthly organic traffic data for Ahrefs blogs, pulled from Site Explorer and plotted on an XmR chart:

Now… this is not very helpful.

There are many data points outside the expected range (red), with some closer to the midline than the quartile boundary (orange).

XmR charts are supposed to show incredible variation in a consistent process—but in this image, almost every data point suggests incredible variation. What do you give?

Process charts are designed around simple manufacturing processes, and they work very well when the expected output of the process is constant.

If your goal is to create 10,000 widgets per week, the XmR chart will help you understand if the 5,600-widget month is a normal “blip” in routine operations, or caused by a real problem that needs to be investigated.

Website traffic is more complicated. There are many variables that affect traffic:

- fluctuating search volume per topic,

- individual ranking position,

- new competing articles,

- search feature,

- seasonal,

- publication frequency,

- Google algorithm update…

That means that performing XmR analysis on a long series of traffic data probably won’t be very useful. Your “blogging process” won’t stay stable for long.

In my case, this particular two-year snapshot of data probably doesn’t come from a single stable process—there may be several probability distributions hidden in there.

But we can make the analysis more useful.

Best practice for XmR charts is to limit your analysis to times when you know the process is relatively static, and recalculate if you suspect something has changed.

Take a look at the Moving Range chart for the data below, most of the traffic variation occurs in November and December. We need to investigate possible causes.

I understand that publishing frequency is pretty static (definitely not doubling content output). Seasonality will cause traffic dips, not spikes (we’re writing about SEO, not holiday gift guides).

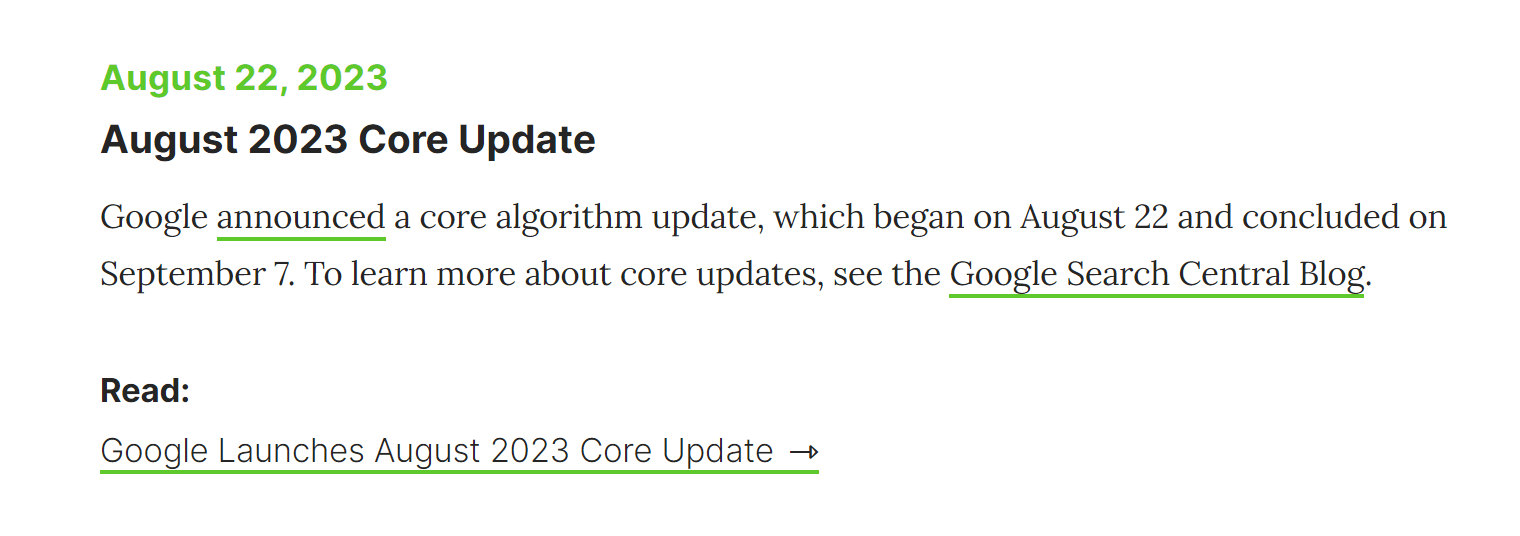

But there is a big Google update at the beginning of December:

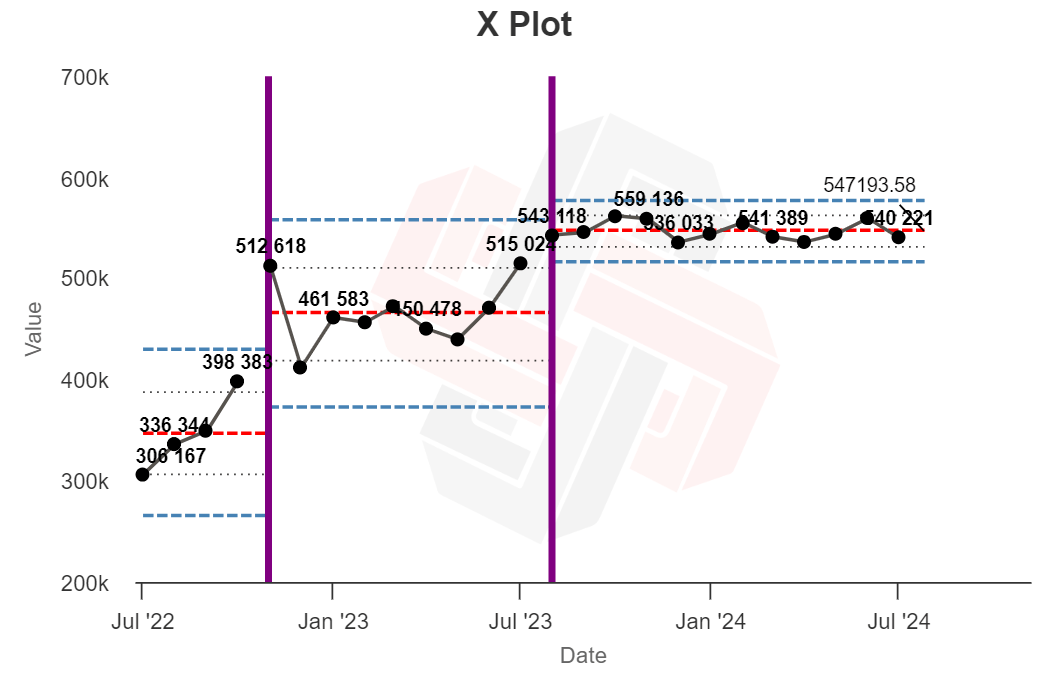

If we can in that assumption something happened to the process of our blog at this time—a possible change to the traffic caused by the Google update—we can add a divider to our XmR chart.

Instead of trying to analyze the traffic as a single process, we can consider it as two processes, and calculate the XmR graph separately:

Now the first process looks stable (all black dots). The second process shows less extreme variation (red), but still has a lot of moderate variation (orange) to appear stable. There may be other processes going on inside.

And according to the rule of thumb for analyzing XmR charts: “The duration of the XmR chart should be reviewed when the ‘long-term’ data remains above or below the Average line.” This trend started at the end of summer (also around the time Google announced another core update):

We can add another divider at the beginning of this “long-run” data to make three separate XmR analyses:

In doing so, all three analyzes appear to be stable, with no significantly different points. In other words, we seem to have done a good job in taking three distinct processes occur in our traffic data.

From this analysis, it seems that there is a good chance that our traffic was affected by external factors during the two major Google updates.

Now… this is basically a post-hoc data abuse exercise. We cannot infer any causality from this analysis, and it is possible that other arbitrary divisions would produce similar results.

But that’s okay. This chart cannot give a clear and concrete reason why Your traffic is changed, but it can tell you where to lookand help you determine whether dealing with traffic or surge issues is a good use of your time.

The main measure of a model’s usefulness is its ability to help you predict everything. Will the XmR chart help me do a better job on the Ahrefs blog in the future?

I think so.

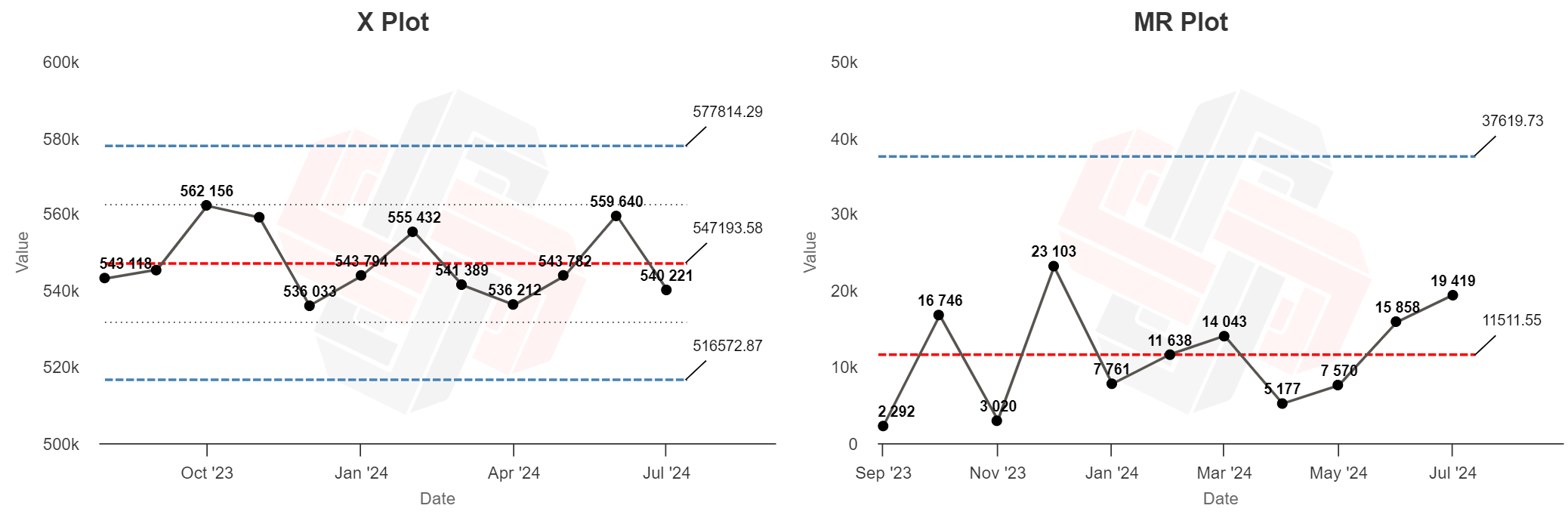

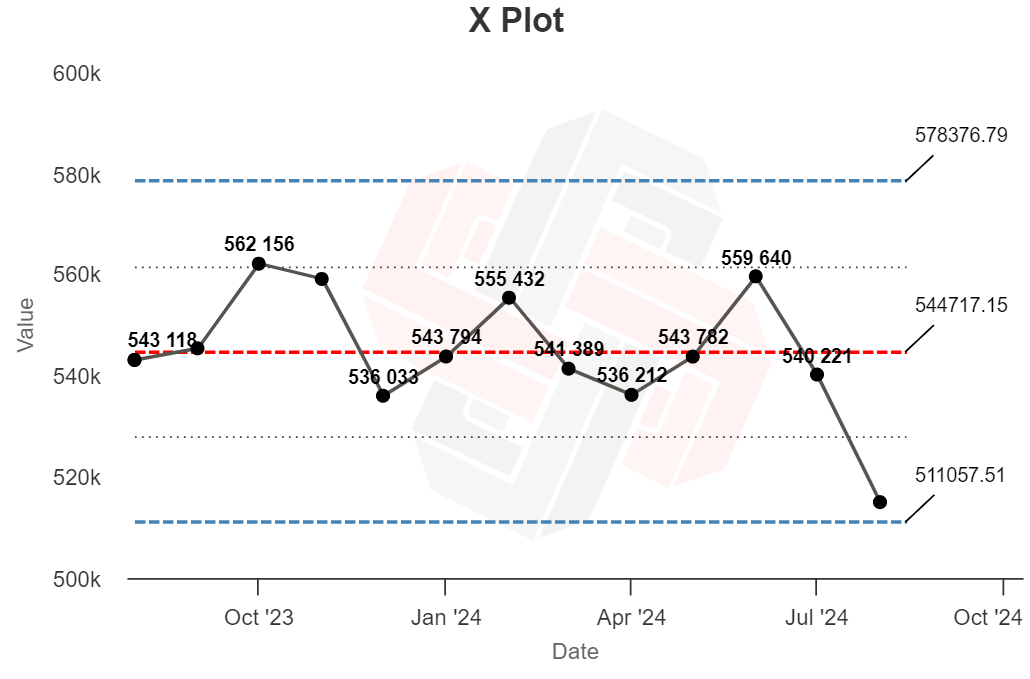

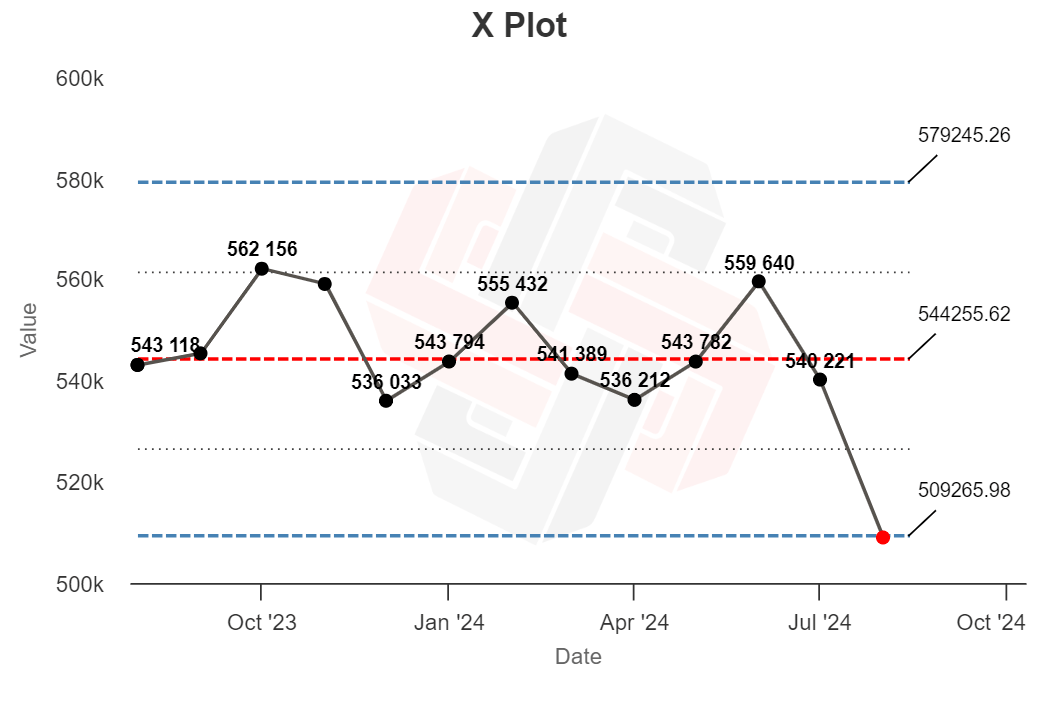

Assuming my “blog process” remains relatively stable—I publish with the same frequency, target the same topics, compete with the same competitors—I now have a “stable” data set that I can use to provide extra context for future traffic numbers. :

Over the next month, I can determine whether dips or spikes in our traffic may be the result of normal variation, or whether there are changes that require my attention – like a Google update.

If, for example, my traffic does this next month…

…I know that—given this distribution—the traffic drop may be a normal, unexciting variance.

But if you do this…

…there may be more in the works.

With extreme traffic changes you can usually “eyeball” the traffic graph and guess what happened. But XmR charts are useful for more subtle variations, and there’s a good chance I’ll be able to identify and act on just one month’s worth of data. It’s pretty cool.

A final thought

Addressing traffic changes is a huge challenge for SEOs and content marketers (and we’re working on a few ways to help you spot these signals among the noise of your traffic data).

In the meantime, I’ve found the XmR chart to be an interesting tool in my toolkit, useful for contextualizing the monthly report numbers and justifying when I should (or shouldn’t) be throwing out energy issues during the down months.

(At the very least, XmR’s chart might just give you the confidence you need to say “get off my back” when that VP sends you a rude 3AM email complaining about the 8% drop in traffic last month.)

Side note.

Thanks to Benyamin Elias, VP of Marketing at Podia, for introducing me to XmR charts.